When he graduated college with a degree in English literature, Jim Fingal had big dreams of a glittering career in publishing. He scored an unpaid internship at The Believer – an independent literary, arts and culture magazine – where he did whatever unglamorous work he was assigned, and was quickly disabused of any notion that the role might lead to something bigger, better or paid. He was wrong.

A few years earlier, renowned experimental essayist John D’Agata had been commissioned to write a piece for Harper’s magazine, which was ultimately rejected for publication. The truth of why is a bit murky: it was either due to disagreements about its fact checking or because the magazine had a new editor by the time it was written, and that editor wasn’t on the same page as the author about his vision for the piece: less non-fiction journalism and more literary reflection. The piece, titled What Happens There, was eventually salvaged for a new life at The Believer, where the editorial staff had full knowledge of D’Agata’s writing style and his take on the essay. It was, however, still given to Jim Fingal to fact check.

‘I was not particularly trained in fact checking,’ Fingal says via Zoom from his home in San Francisco, ‘but I was very enthusiastic.’ It was late 2005, and the young intern worked on this task part time over a few months. He knew his job was basically busy work, but in his enthusiasm he was determined to do his duties well. ‘And so life one of The Lifespan of a Fact was me doing a more or less straight fact check of the essay,’ he says, ‘but in this bizarro land where we already knew that a lot of it was manufactured or finessed.’

‘I think John was both horrified and fascinated by it. I think he saw in it a similar level of obsession, but focused in a different way than his approach to writing.’ – Jim Fingal

Life two, to use Fingal’s terminology, began when the managing editor of The Believer sent D’Agata the ‘70 or 80 or 90-page’ Word document that Fingal produced in the course of fact checking the author’s 10-page essay. ‘I think John was both horrified and fascinated by it,’ he says. ‘I think he saw in it a similar level of obsession, but focused in a different way than his approach to writing.’

It was at this point, well before his essay was even published, that D’Agata approached Fingal with the idea of creating a book. He was immediately on board with the proposal. ‘I was very excited,’ he says. ‘I was young, and I wanted to do the literary thing, and this was an exciting opportunity.’ Fingal even came up with the concept for the layout featuring the red and black text: ‘John’s idea immediately made me think of this palimpsest, illuminated manuscript kind of thing, with the comments around the text.’

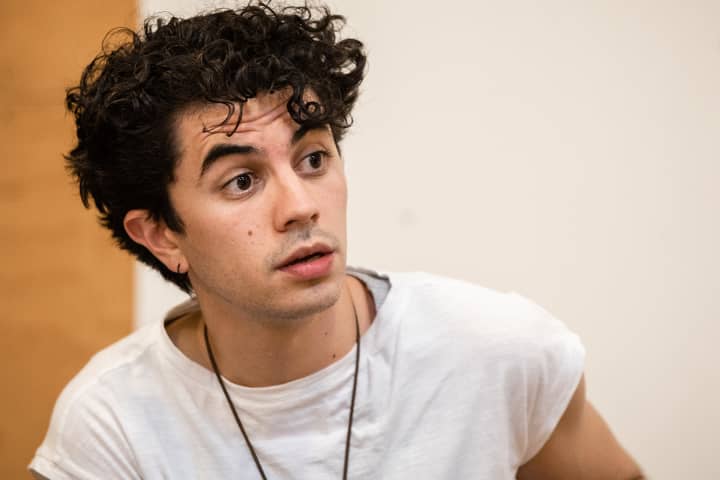

Karl Richmond plays Jim Fingal. Photo: Charlie Kinross

Life two: from essay to book

Over the next year or so, they worked on the draft by sending Word documents back and forth. Fingal claims D’Agata was ‘largely incapable of using Track Changes’ so they instead relied on comparing versions, which meant they ultimately lost track of who wrote which parts. ‘It’s not like he was assigned his character and I was assigned my character,’ he explains. ‘There’s a fair amount of back and forth there. But I don’t know that there’s any of the actual exchanges between John and I from the initial fact check,’ he says, admitting that it would be pretty boring to read their original emails because they were so polite to each other. ‘John was apologetic that this poor intern had to go through this – at least he was outwardly; maybe he was inwardly annoyed with me! But a back and forth between two collegial people discussing the facts of an essay would probably have a much smaller audience,’ he jokes. ‘So if you read the book from page one to the last page, that’s absolutely not how a fact-checking job goes.’

Essentially, both author and fact checker took certain fictional liberties for the sake of the story. The Lifespan of a Fact is less non-fiction journalism and more literary reflection, just like D’Agata’s original essay. ‘I think you can read the book as an essay in the spirit of how John defines an essay,’ Fingal concurs.

‘The essence of our points of view are in the characters of Jim and John in the book ... I certainly played up my saltiness and John says that he let his inner diva come out in the John character.’ – Jim Fingal

By way of example, Fingal confirms that he did not actually write a fact-checking batch automation script to do the job faster. Neither did he fly to Las Vegas during the fact check – ‘I was an unpaid intern. No one’s flying me to Vegas to check things!’ He did, however, fly to Vegas after he and D’Agata decided to write the book. ‘It was generating material for a more dramatic scene to actually be able to check that stuff,’ he explains. ‘I originally googled it. But I think it was much more interesting and striking going to the location of the Stratosphere Hotel, and getting the material for the red brick pavilion, for instance, which indeed didn’t appear to be the colour that it was described as in the essay!’

The now co-authors finished their draft in 2007, and initially found a small indie publisher who was interested in the book. But momentum stalled: D’Agata’s previous book, About a Mountain, had been published by WW Norton, who had the option to his next manuscript. But because the events discussed in What Happens There (and by extension, The Lifespan of a Fact) were also featured in About a Mountain, Norton wanted to wait. It was another five years before they eventually published The Lifespan of a Fact.

‘It got a much larger audience with Norton,’ Fingal acknowledges, ‘but for a long time we’d check in once a year and be like “yep, still nothing’s happening.” It’s kind of funny,’ he continues, ‘because when the book eventually came out in 2012, there was literary fanfare and it struck a chord with reviewers and writers and editors – which is good if you want publicity for a new book – and I think it got optioned immediately to become a play but then it was another six years until that came out. So, the lifespan of The Lifespan has been very extended.’

Life three: from page to stage

A page from the book and a page from the script

Once the rights were optioned, Fingal and D’Agata essentially handed the story over to playwrights Jeremy Kareken, David Murrell and Gordon Farrell. ‘I was not involved at all. I didn’t even see the script before seeing the play,’ Fingal says. Once a year, he’d get a cheque to extend the royalties, but after the experience they had with the book, he frequently assumed it was never going to happen. It was a pleasant surprise, therefore, that his first experience of the play was when he was flown to New York to do a photo shoot for the New York Times with the original Broadway cast of Bobby Cannavale, Cherry Jones and Daniel Radcliffe (who was playing Fingal).

D’Agata was a bit more involved with the playwrights, Fingal says. ‘John gave his blessing for them to do whatever they wanted or needed with it – in the spirit of the essay and of the book – in order to make it interesting and successful on the stage. And I think he went to a table reading, so he was more aware of what was going on. But I think he still largely ceded to the experts in how to make an engaging and successful stage performance.’

‘The character is a fictionalised version of a fictionalised version of me, so I don’t feel like it misrepresents me in any way because that was never the point.’ – Jim Fingal

As to how he felt when he finally saw it, he laughs. ‘I enjoyed it, but the character is a fictionalised version of a fictionalised version of me, so I don’t feel like it misrepresents me in any way because that was never the point.’

In 2021, The Lifespan of a Fact is being staged by both MTC and Sydney Theatre Company, in two separate productions. Asked what he thinks it is about this work that resonates so much right now, Fingal becomes reflective. ‘It’s ironic. What Happens There was closed in 2006 or 2007 but didn’t get published until 2010 because in the aftermath of the Iraq invasion and WMDs, The Believer considered it not the right time to publish an experimental commentary on truth in what might be mistaken as journalism. The play first came out in 2018, which I have to imagine was related to Trump. So if the Broadway performance was a kind of slow echo 2016, I could see this being a faster ripple from 2020. Either way, it’s something that sadly is evergreen.’

Today, Fingal works in IT but he keeps his publishing hat on as co-founder of a magazine about technology. He remains friendly with D’Agata, who is now the director of the non-fiction writing program at the University of Iowa’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. He’s ‘a very successful teacher whose students love him,’ Fingal says but he is yet to publish another book (although he is apparently working on a translation of Plutarch). ‘He no doubt has his own reasons,’ Fingal muses, ‘but I imagine some amount of it was him wanting to make sure the next one is something like a lost history, something less personal.’

Elaborating, he explains that the end result of this long journey appears to have been less positive for D’Agata, who was often pilloried by readers and reviewers – of the book more than the play – who ‘interpreted him as [someone] who is mean to interns, and who holds ludicrous views’. Both authors were surprised by this reaction, and Fingal muses on the irony that so many people were ready to write about the book without reflecting all that deeply about its text; without fact checking it.

The Lifespan of a Fact is on at Arts Centre Melbourne, Fairfax Studio from 15 May 2021. Buy tickets now. The book is published in Australia by riverrun / Hachette.

Published on 28 April 2021