Sir Christopher Hampton is an award-winning playwright, screenwriter, translator and film director. He has translated into English multiple works by French playwright Florian Zeller, with whom he recently won the Academy Award for Best Adapted screenplay, for The Father. But his introduction to Zeller was via The Truth…

What is it about Florian Zeller’s works that attracted you to them?

I think it’s a combination that is very, very rare: his plays are very original, but they’re also extremely simple. That’s a very rare combination. I can’t quite think of anyone else who embodies that combination so clearly.

The Truth was actually the first of his plays that I saw. It was in 2013, before I knew him. I went to see it in France, and I remember coming back to London and telling people about this very interesting young writer – who I thought was a comic writer, because this was the first play of his that I’d seen. I said that I thought it needed quite careful handling, but if we could find the right director and the right theatre, it would be worth going forward with it. But it’s quite a struggle to get London theatres to do unknown foreign playwrights, so we didn’t get very far with that.

The following year The Father was a big success, and I thought ‘oh it’s this boy again, I’ve got to go and see it.’ I let him know that I was coming over and then just turned up and saw The Father, in the original French. And afterwards, there he was. So that’s when we met for the first time, and I said to him: ‘This would be a perfect play to introduce you to English-speaking audiences. So can I translate it?’ I think he was quite pleased by that.

‘My philosophy of translation is to be as accurate as possible, but to make sure that it’s written in a way that will connect with an English-speaking audience.’

It was only the beginning of a long process, though, because it was quite hard to get anyone to even do The Father as well. But there’s a chap called Laurence Boswell, a director, who ran a studio theatre in Bath called The Ustinov; they specialised in contemporary European plays, so we got it on there, in a 100-seat theatre. It is, as you know, an extremely powerful, moving piece and it got the most wonderful reviews, but we still couldn’t get anyone to move it to London for a while. Eventually, The Tricycle – as it then was but it’s now called The Kiln – took it as a sort of off-Broadway project. And it got another lot of great reviews and eventually enough arms were twisted for it to go into the West End. But up until then I don’t know how many times I heard people saying ‘do you think the public wants to see this sort of thing?’

You’ve translated six of Florian’s plays since then. What is it about your working relationship that makes it so successful?

I’ve actually translated seven of his plays. There’s a new one that hasn’t come out yet anywhere; it hasn’t even come out in France yet. As to what makes our relationship work, I think we just get along very well. It’s that simple. For example, when I sent him the translation of The Father, which was the first play of his that I translated, he just wrote back ‘Well, I think this is very, very good and I’m very happy with it’ – which is what you want to hear.

Writing the screenplay for The Father is a good example of how we work: we had a discussion about exactly what we wanted to do with the film, and then he wrote a draft in French and sent it to me; then I wrote a draft in English but I changed things and sent it back to him; then he wrote another draft in French, and changed some more things; and then I did a fourth draft, in English, and then we met up in person and went through the whole script line by line. That took about a week, and that was that. And that was then what he shot. I wasn’t at all surprised that he turned out to be really a good film director too!

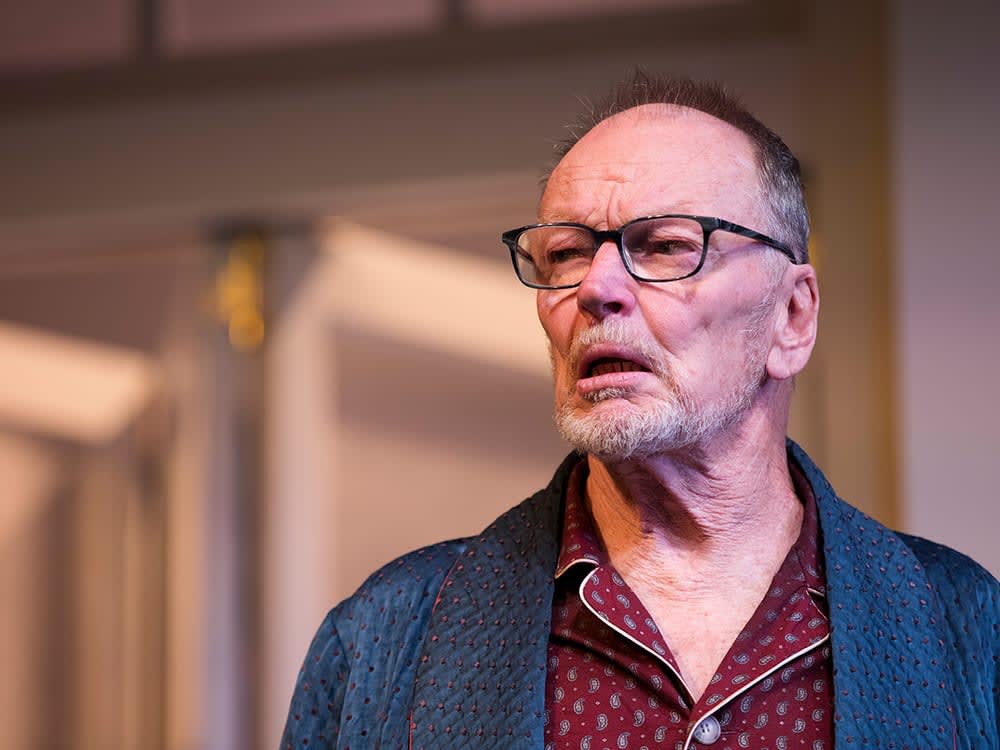

John Bell in The Father, 2017, an MTC/STC co-production. Photo: Philip Erbacher ©

What are the most important factors to consider when translating a play from one language to another?

My philosophy of translation is to be as accurate as possible, but to make sure that it’s written in a way that will connect with an English-speaking audience. Which might mean changing a joke here and there, for example, but generally speaking you work out where the author wants the audience to laugh and you make sure that they do.

I started translating when I was very young. I worked at the Royal Court Theatre in London as a kind of resident dramatist. And one of the things they did was ask you to do new versions of classics. So I started with Uncle Vanya, and I found I enjoyed it very much. It also seems to me, now, that an important part of my job is to keep an eye out for new writers. I speak French, and I speak German. So I can keep an eye out for what’s happening in those countries.

How do you ensure that nothing is lost in translation, that you maintain the original integrity of a work you’re translating?

Well, I must say with Florian in particular, the simplicity that I mentioned before helps. His language is very straightforward. I also translate Yazmina Reza, whose plays are much more complicated in terms of the elaboration of the language.

I also do different versions for America. It started with Reza’s ‘Art’, because when we began rehearsing it in the United States it occurred to me that it was a different language. So I made a certain number of changes but we still maintained the fiction that the characters are French and it’s all taking place in Paris. But we took it even further with God of Carnage [another of Reza’s plays translated by Hampton] because James Gandolfini was playing the lead and on the first day he said ‘no one will ever think I’m French’, which was undeniable. So with Yazmina’s agreement, we re-set the whole play in Brooklyn, and gave it local references that were the equivalent of the French references.

The Truth hasn’t been done in New York yet. They’re trying to cast it at the moment. But when they do, I’ll likely do something similar for the American audience.

But not for Australian audiences?

Australians are more adaptable. I have had conversations before with Australian peers where I’ve said ‘look, you’ll find that there’s an English version of this play and there’s an American version of this play. Just look at them and make your own decisions.’

‘Since the play was written, we’ve moved into a world where it’s become rather crucial to be able to distinguish when people are telling the truth or not.’

You mentioned before that The Truth was your first introduction to Florian Zeller. What was it about this particular play that appealed to you?

Well it’s a play with universal application. Everybody understands it. But also, crucially, it’s very, very funny. It was such a pleasure when we put the play on in London, to go and stand at the back and hear the audience just roaring with laughter. It’s always one of the most pleasurable things about being a playwright: to hear the audience laughing. And if you have skilled actors with this text, it is very, very funny.

Stephen Curry and Katrina Milosevic rehearsing The Truth. Photo: Charlie Kinross

The play was written 10 years ago. Given the events of the past few years, do you think audiences now might come in with a new appetite for a play about the concept of truth?

The play juggles around with all these sort of metaphysical ideas about whether you should tell the truth, and when should you tell the truth, and how much of the truth should you tell. And since the play was written, we’ve moved into a world where it’s become rather crucial to be able to distinguish when people are telling the truth or not. Whole sections of the world have been given over to systematic lying in a way that hasn’t really happened since Goebbels.

In addition to your translation work, you’re also a playwright as well as a screenwriter and director? Do you have a preference for one form or the other?

I actually really like skipping from one to the other. But I suppose if I was only allowed to do one thing, it would be the theatre. This play of mine, A German Life, that Robyn Nevin is doing in Australia right now, that was a really extraordinary experience for me. I’d never written a one-person show before, and I think that’s probably what I look for: I try to find something that I haven’t done before, a new challenge. I quite like difficult challenges.

Published on 31 May 2021