The Truth is a play about perspective. The play’s director, Sarah Giles, has been having a blast toying with visual perspective in a way that matches how playwright Florian Zeller toys with audience and character perspectives. The result is almost Escher-esque.

Giles wasn’t all that familiar with Florian Zeller’s writing before she began working on The Truth. But she immediately fell for the script when she first read it. ‘I found it very funny,’ she says. ‘I’m passionate about humour and the maths of humour. And the play’s humour just stood out to me straight away, as well as its style and the tone. It sits in a territory that is a bit absurd: a sort of Eugène Ionesco meets Samuel Beckett meets Seinfeld meets Aaron Sorkin place!’

Elaborating, she explains that ‘It’s slightly otherworldly, in the way they speak: it’s very bouncy, it’s very fast, and the characters run verbal rings around each other. But what Zeller does super well, I think, is to ensure there’s also heart in the play, in the midst of the absurd. It’s often hard to get that stuff into this genre, so it feels like it’s almost a new genre in some ways.’

‘It’s this wonderful kind of avalanche of interrogating reality, and interrogating what you think you’re seeing.’

It wasn’t just the play’s inherent comedy that appealed to Giles, though; she also admires how smart it is. The philosophical ideas that Zeller plays with – the advantages and disadvantages of truth telling and of lying – are used to interrogate what we’re seeing and hearing, she says. This is a play about not taking things at face value. ‘I think at this point in time, in history and political history, that feels quite relevant.’ She acknowledges that The Truth is by no means a fiercely political play, but notes that its insistence on taking nothing at face value feels important right now. ‘And it does that rare thing of entertaining you while making you think. As opposed to a traditional farce, which makes you laugh but there’s really not a lot of deep philosophical or intellectual thinking that goes on.’

For a piece to tick both boxes is quite rare, Giles believes, and The Truth does it with abundance. And not just through its content, but also its form. ‘The way it’s structured is just so clever and tight and neat, which makes it a really satisfying piece of writing and piece of theatre,’ she says. As a result, the whole play feels a bit like ‘a kind of extended theatre sketch or joke’. Explaining, she points out that Zeller interrogates reality through what he has his characters say and do, and also through the way he’s structured the work, with each scene opening up questions about the scenes that preceded it.

‘It’s not just what the actors say that tells you the story, the message, of the play,’ she says. ‘It’s how the play is made. He does it in his other writing too – for example, the way The Father mucks around with reality and what you think you’re watching is similar to the way The Truth works: the accumulative effect of watching the scenes, the formal journey of that, conveys meaning as much as if not more than the content of what the actors say. It’s this wonderful kind of avalanche of interrogating reality, and interrogating what you think you’re seeing at each step.’

Up for the challenge

While this all makes for a highly entertaining and intellectually satisfying piece of entertainment, it also presents many challenges for Giles and her cast. But this is just one more reason why she loves the work. ‘It’s a very technical exercise in lots of ways, with the speed and the rhythms of it all,’ she explains. ‘But the technical challenge of it is so fun! When you go bang bang bang bang pause, and you find exactly where the laughs should come. That’s what I mean about the maths of humour. And those guys are all absolute living legends in terms of that kind of stuff.’

Those guys are her cast: Stephen Curry, Michala Banas, Bert LaBonté and Katrina Milosevic. All well-known comedic actors, their challenges in The Truth are quite uncommon. While Curry gets to play what Giles refers to as a naturalistic through-line and his scenes have an accumulative story, the other actors don’t have this. ‘They have to play each scene for its face value,’ she notes. In a show that’s all about not taking anything at face value. ‘It’s about finding the restraint: we don’t want to play the play, we want to play the scene. So that’s been hugely challenging because it’s unusual for actors to not have a psychological through-line, to not have a naturalistic journey.’

Stephen Curry and Michala Banas

Photo: Charlie Kinross

Bert LaBonté and Stephen Curry

Photo: Charlie Kinross

Stephen Curry and Katrina Milosevic

Photo: Charlie Kinross

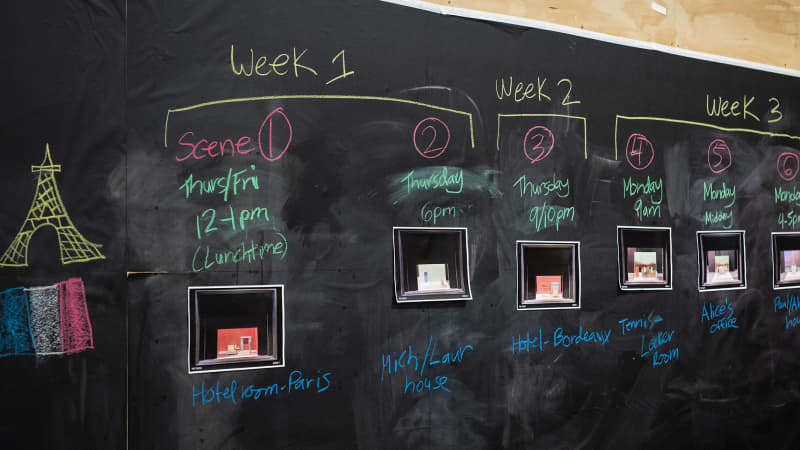

Mapping out rehearsals

Photo: Charlie KinrossAbove: view a rehearsal gallery

Can you trust what you see and hear?

Giles has very much enjoyed leaning into many of the psychological and philosophical themes in the staging of the play. Taking Zeller’s lead in presenting the story through both content and form, she has worked with set designer Marg Horwell and composer & sound designer Jethro Woodward to highlight these ideas visually and aurally.

‘There’s a version of this play that is very visually straightforward,’ she muses. ‘It’s literally just about what the actors say. But theatre is a great place to interrogate lying – after all, theatre is the greatest lie of all, albeit an agreed upon lie. So what the design team and I have been trying to lean into is having some fun with those ideas of interrogating what you see in front of you. There’s a sense that, through how we get from one scene to the next, we can interrogate the language of theatre, and the lies, and have fun with that in the same way Zeller’s having fun with us.’

‘It sits in a territory that is a bit absurd: a sort of Eugène Ionesco meets Samuel Beckett meets Seinfeld meets Aaron Sorkin place!’

Asked to provide an example, she begins to explain a visual joke that she agrees is almost Escher-like. ‘We set up various theatrical conventions or languages early on in the show, and then they subtly shift over time. It’s not like we’re going from theatrical realism to something else. It’s that we’re just changing the rules and asking people to interrogate what they’re seeing as much as what they’re hearing.’

She mentions a staircase that begins as a picture but later becomes three-dimensional. Or a fridge that starts out functional and three-dimensional but when we return to that location the fridge in that transition is now light enough to be carried by Michala Banas on her shoulders. Or a picture that starts as a naturalistic representation of clouds, then turns into something else and eventually becomes a giant projection of static that is actually snow. ‘It keeps shifting, so we’re asking the audience to keep reading things in a new way. The transitions give you a different perspective.’

It’s similar with the music, she says. The Truth is ‘a really neat little play that feels like a musical quartet, with these four characters. So Jethro Woodward and I have been talking a lot about quartets and a lot about the sounds that we hear and how they might subtly change but always remain recognisable. I’m just trying to funnel everything that we’re doing in this production into the same direction so it feels very cohesive. It’s just fun, and really funny, and really satisfying.’

Read more, including a Q&A with Sir Christopher Hampton as well as cast and creative biographies, in the show programme.

Published on 15 June 2021