James Tucker loves the moments in a performance where you can almost hear the audience gasp "how is that possible?" As the Fly Supervisor at Southbank Theatre, he’s part of a team that makes it possible.

When a set piece descends from above the stage, or a backdrop flies up and out of sight to reveal a new scenic world behind it, there’s at least one person working behind-the-scenes. In fact, the curtain wouldn’t rise at all without a fly supervisor.

Above the Sumner stage is a 20-metre void called the fly tower. At its apex are 50+ fly bars, to which lighting and scenery can be attached and ‘flown’ into view. Most theatres with a fly tower have ropes running down a wall side-of-stage in what’s called a counterweight system. However, the Sumner has a state-of-the-art Power Fly System, where motorised winches can be programmed and operated by a computer. This computer, called a Nomad, controls all the fly bars’ motion, and cues can be put into a sequence for easy and reliable playback. This system enables designers to be more adventurous, and also has many safety features.

THE FLY FLOOR

Visitors backstage may be surprised to find that Tucker is not standing on the off-prompt side of the stage deck. Instead, he’s 10 metres above it, halfway up the fly tower on what’s called the Fly Floor. ‘The Fly Floor is located halfway in the tower space so that there is a clear view of the space 10 meters below and 10 meters above,’ explains Tucker. ‘It is essential to have a clear view of all the flown elements from stage level to 20 meters out. If you are on the stage and flying you would be looking up into darkness and the blinding lights of the LX rig.’

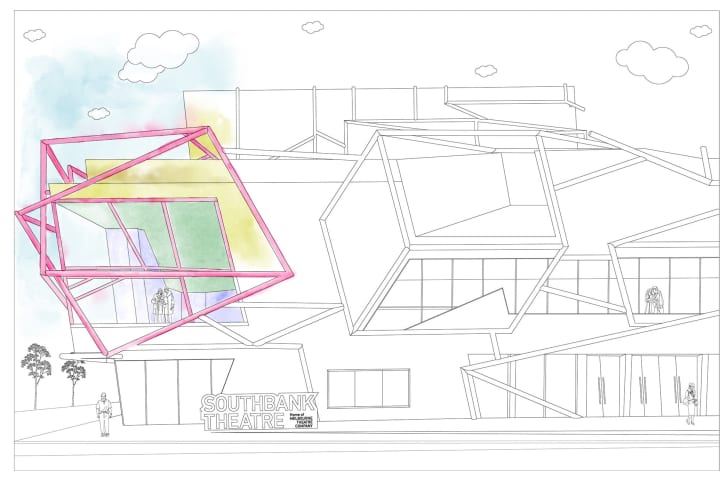

The Gloria set seen from the Fly Floor. PHOTO: Brett Boardman.

The Gloria set seen from the Fly Floor. PHOTO: Brett Boardman.

AMBITIOUS SHOWS

When asked which MTC production has had the most complicated flying demands, Tucker says it’s hard to pick. ‘There have been many,’ he reflects, ‘Macbeth, Richard III, Twelfth Night, Queen Lear, Gloria, Vivid White, Wild…’ The list goes on, indicative of the ambition and achievement of MTC staff and artists. The Company’s 2017 production of Macbeth included 27 scene transitions and 34 fly cues, while Gloria in 2018 saw the set entirely transform from a replica Starbucks to a film studio’s office in 97 seconds of theatre magic. ‘Those big and quick transitions are what is most memorable’ says Tucker. ‘The House Curtain comes in and two or three minutes later it goes out and reveals a completely different scene where you can almost hear the audience gasp “how is that possible?”. Wild was such a transition with the whole stage tilting about 60 degrees, ceilings flying up, beds and hotel furniture disappearing into the walls.’

SAFETY FIRST

Productions with complex flying sequences such as these are not without their hazards. Did you know that it’s considered bad luck to whistle in a theatre? In theatres with counterweight systems, fly operators (historically off-duty sailors whose experience rigging sails brought skill with knots and ropes) used to communicate with each other by whistling. Whistling backstage was therefore banned, lest you accidentally trigger a fly cue. While this superstition may still exist with some older crew there are now more modern methods that add to the safety protocols. For example, Tucker explains that bars can be grouped together in a way that if one fails the others will stop. ‘This safety feature is essential for group lifts such as ceilings or multi-point trusses.’

‘Those big and quick transitions are what is most memorable. The House Curtain comes in and two or three minutes later it goes out and reveals a completely different scene.’ – James Tucker

Impressively, variables like speed, acceleration, deceleration, time commands and destination can all be programmed to have millimetre and microsecond accuracy that can be used to create transitions that synchronise perfectly with sound, lighting and automation cues. ‘Delays and triggers (where one axis causes another axis or axes to stop, start, pause, resume, speed up or slow down based on the triggering axis’ position) can be daisy chained in almost unlimited sequences to create very complex fly cues and transitions.

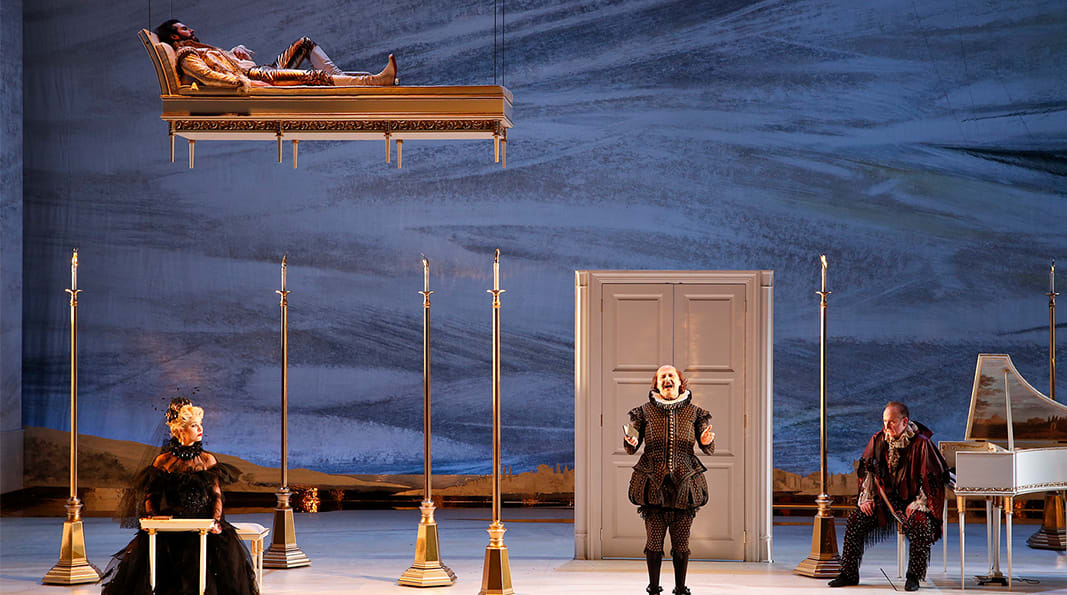

Christie Whelan Browne, Lachlan Woods, Russell Dykstra and Colin Hay in Twelfth Night. PHOTO: Jeff Busby.

Christie Whelan Browne, Lachlan Woods, Russell Dykstra and Colin Hay in Twelfth Night. PHOTO: Jeff Busby.

BUMP-IN

In the days before the first audience take their seats, the theatre is a flurry of activity as the set, lighting and sound equipment arrive during bump-in. As Fly Supervisor, Tucker is an integral part of a team that installs the flown elements. ‘They’re assessed for weight and how best to attach each to the fly bar to ensure a balanced load that is within the lifting capacity of the system,’ explains Tucker. ‘The integrity and working load limit of the attachment points and lifting equipment is inspected by the Head Mechanist. The load is levelled to ensure a uniform distribution of the load across the fly bar.’ Tucker then makes sure there is enough clearance to fly the flown element past other flown pieces. The importance of the MX (mechanist) and Stage Management crew can never be underestimated once the production is in operation. They are often the eyes of the Fly Supervisor, giving clearances, and responsible for starting and stopping cues, much like a ‘dogman’ is to a crane driver .

TIME FLIES

Since Southbank Theatre opened in 2009, Tucker has flown countless pieces of scenery across hundreds of performances. His favourite memory, however, remains this theatre’s opening Gala Performance. ‘It was such a relief and sense of achievement to see the system up and running after having spent 18 months working on the theatre’s construction and the installation of the fly system,’ reflects Tucker. It’s an astonishing journey, one that makes you wonder: how is that possible?

Published on 10 June 2020