Inspired by lived experience, Torch the Place is the story of three siblings returning home to visit their mum, who is displaying the signs and symptoms of hoarding disorder.

‘Hoarding’ is a word that has become synonymous with reality television. Hoarders, the TV show, took off in America in the same way American Idol did, with audiences quickly becoming fascinated by this complex disorder that seemingly buried its sufferers alive. But such shows can ignore the seriousness behind the attention-grabbing headlines.

People can die from hoarding disorder in the same way they die from afflictions such as depression. It’s a clinical mental illness, closely associated with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Attention Deficit Disorder. To healthy minds, it’s inconceivable that a person suffering from anorexia cannot eat a single banana without experiencing immense distress. Equally, it’s inconceivable that a person afflicted with hoarding disorder would choose to keep old banana peels in a bucket on their bathroom floor, but the same levels of distress ensue should they be forced to throw those banana peels away.

Law and Dis-Order

Hoarding disorder might seem like a complex problem to turn into a comedic play, but in Benjamin Law’s debut stage work, Torch the Place, that’s exactly what he’s done. The narrative is punctuated with the kind of gasp, snort and laugh-out-loud humour we’ve come to expect in Law’s writing. But it also doubles down on the seriousness of hoarding as an illness, and rips apart our collective knowledge of this affliction to help us understand the tribulations of those encumbered with the disorder.

In the play – which Law created through MTC’s NEXT STAGE Writers’ Program – three adult-children return to visit their mum with a skip in tow to restore order in her shambolic home. Over the course of the play, we learn why this mother is so desperate to cling to the past.

Diana Lin, Charles Wu, Michelle Lim Davidson and Fiona Choi in rehearsal, as mum and her three adult children. Photo: Charlie Kinross

Memory and Possession

Almost all of us can identify possessions or objects of enormous personal value, which others might deem worthless. An heirloom trunk that travelled from Italy with your immigrant ancestors, or a medal from war passed down through generations symbolising the very survival of a blood line – these are the possessions that hold incalculable personal value.

Researchers at the University of Bath assert that physical objects can become extensions of vivid memories for people with hoarding disorder. Lead researcher Dr Nick Stewart explains: ‘We can all relate to the experience of being flooded with positive memories when we hold valued possessions in our hands. However, our findings suggest that it’s the way in which we respond to these object-related memories that dictates whether we hold onto an object or let it go. The typical population appears to be able to set aside these memories, presumably to ease the task of discarding the objects, and so manage to avoid the accumulation of clutter. The hoarding participants enjoyed the positive memories but reported that they got in the way of their attempts to discard objects.’

Hoard and trauma

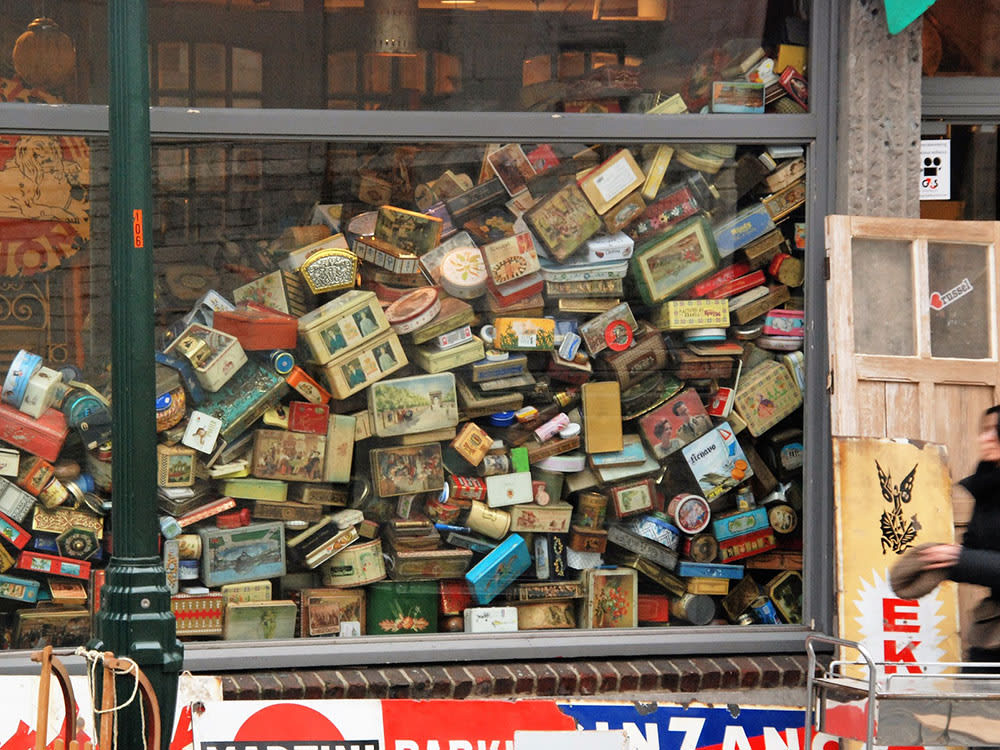

Hoarding disorder becomes a disease when the objects being saved cause harm to the sufferer or those around them. For instance, collecting daily metropolitan newspapers and being unable to throw them away will quickly take over the real estate of your study, then living room, then bedroom and so on. Until there is no space to eat, bathe, sleep or live comfortably between thousands of bundled-up broadsheets. In Sarah Krasnostein’s book The Trauma Cleaner she details the accounts of one woman’s effort to clean up the detritus of numerous sufferers of hoarding disorder. Krasnostein describes the homes she visits as ‘caves of filth’ where untangling a ‘solid glacial mass of garbage fused together’ was just another day on the job for her subject, Sandra Pankhurst. Krasnostein asserts that hoarding is a response to trauma, and the greatest defeaters of trauma are order and belonging.

Photo: Eveline de Bruin from Pixabay

Research from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine indicates that people with hoarding disorder often experience disordered sleep, which in turn exacerbates their hoarding. Pamela Thacher, author and assistant professor of psychology at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, says: ‘Hoarders typically have problems with decision making and executive function … if hoarders have cluttered/unusable bedrooms (and less comfortable, functional beds), any existing risk for cognitive dysfunction, depression and stress may increase as sleep quality worsens.’

Sense and stigma

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is widely considered the most effective method of treatment for hoarding disorder. Past memories, cumulating in a physical mass, regularly deprive hoarding disorder patients of their ability to create new memories. Through CBT, patients develop strategies with psychologists to acknowledge that their pasts are stealing from their futures and in order to make room for new memories, they must de-clutter their lives.

Like any mental health disorder, hoarding has attracted a severe stigma in recent history. Blame, disdain, mockery and ostracism of patients with hoarding disorders are commonplace. The public’s perception of all mental health disorders is incumbent on us – the public. It is our responsibility to educate ourselves and help each other where possible. Benjamin Law’s play attempts to unpick the intricacies of this complex disorder and inject enough light and laughter into the mess to make sense of it.

See Torch the Place at Arts Centre Melbourne, Fairfax Studio 8 February to 21 March.

Published on 22 January 2020