Writing in the Argus in 1955, critic Biddy Allen announced the arrival of Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll in language that would be echoed down the years: ‘Barney, Roo, Pearl and Emma are real people. We know their faces, their voices – we share their dreams, we understand their failures.’

Allen couldn't have known it, but this claim – that here, finally, Australians could see themselves on stage – would go on to elevate The Doll to mythic status. No other Australian play can claim to equal its significance, and that’s not hyperbole. As the Sydney Morning Herald noted at the time, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll ‘may well be found to mark the coming-of-age of Australian drama.’

Australian dramatists weren’t entirely absent prior to The Doll. Louis Esson had created fine work, and pockets of local writing were performed by small companies. But art that redraws a landscape can obscure what came before, and The Doll looms so large on the theatrical horizon that many histories of Australian theatre simply start there.

It was originally staged by the Union Theatre Repertory Company, a new outfit led by British expat director John Sumner, with Lawler himself playing Barney. The production toured Australia and eventually enjoyed a seven-month season on the West End after the rights were purchased by none other than Sir Laurence Olivier. Other productions were well received in Germany, Norway and South Africa, though New Yorkers weren’t as welcoming when the original Australian production arrived on Broadway. Lawler had been compared to Tennessee Williams, whereas in reality the nuanced nature of his play is closer to Chekhov. It doesn’t judge its characters, or moralise, or set heroes and villains in opposition. America didn’t get it.

‘For me, Ray is the unchallenged ‘father of Australian theatre’. I read him, of course, as a student, but my first experience of his work live was not until one month into my tenure at Sydney Theatre Company in 1985, when we opened the magnificent suite of plays comprising The Doll Trilogy as an epic, landmark event. Many of the actors and creative team of that production have remained lifelong friends, forged through the lens of Ray’s towering work. My next encounter with Ray was when I joined MTC and the consistent grace and generosity he has always displayed towards the Company has been an inspiration.’ – Brett Sheehy, MTC Artistic Director

The Doll’s reputation in large part rests on its ‘Australian-ness’, and it’s true that many of those New York audiences struggled with its accents. But the notion that Lawler had captured the essential character of his country along with the vernacular in which they spoke might not comprise the full story. When it was first performed in 1953, post-war Australia was no longer just an outpost of the British empire. The plays that dominated Melbourne stages were mostly dusty imports from London or thereabouts; they didn’t have that much in common with the contemporary experience. American culture was making local in-roads, too, and the increasing tourism and trade of the prosperous 50s afforded a greater sense of existing within a diverse global community.

The Doll, then, didn’t confirm Australian identity so much as forge it – it was a galvanising act, presenting characters around which a nation could rally. It’s important that the play extends sympathy towards every one of its characters, so that audiences could feel that same sense of care extended towards their own person, whoever it was on stage they ended up identifying with.

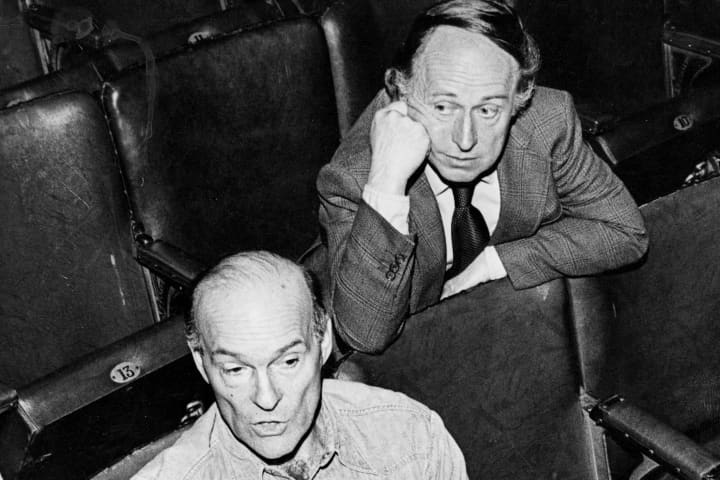

Ray Lawler and John Sumner in 1977

Photo: National Archives of Australia

Candid photo of Ray Lawler on set

Photographer unknown / MTC archives

Ray Lawler with Peter Batey in Twelfth Night, 1955

Photo: Ernest Cameron / CAE

Ray Lawler with Marion Edward in In Duty Bound, 1980

Photo: David Parker / MTC archives

Tim Hughes, Margaret Cameron and Ray Lawler in In Duty Bound

Photo: David Parker / MTC archives

Ray Lawler (right) with John Bowman in The Hothouse, 1981

Photo: David Parker / MTC archivesThis generosity seems characteristic of Lawler himself, by the way. ‘They tell us that the other fellow is nothing but a villain who lies and whose motives are suspect,’ he said when promoting a 1995 production of The Doll. ‘The politician who could really get me is the one who says, “I know the other chap and he’s a good, decent bloke with the interests of the country at heart, but I think our side has the better case.”’ That low tolerance for high drama might seem alien today, but it’s present in much of his writing. It’s often attributed to his working-class roots.

Biddy Allen’s review of The Doll’s first production ends with: ‘Lawler, a Victorian, born in Footscray, is 34, and is single. He has written a few other plays.’

In fact he’d written eight plays before the one that catapulted him into the public eye. The Doll might be set in Carlton, but its spiritual home is Melbourne’s west. Lawler worked in a Footscray foundry between the ages of 13 and 24. His first play was written at 19, and it’s tempting to imagine that some of Hal’s Belles was forged while he was toiling away at the factory. By 1952 his script Cradle of Thunder, set in Williamstown Harbor, won him a National Theatre play contest. This must have been proud news to a writer whose grandmother was illiterate, and who died leaving an old tin containing every scrap of writing that had ever passed into her hands, on the off chance some of it might be important.

‘I still think that’s one of the most pathetic things I ever heard of,’ he later said. ‘Mixed up with the last letters from her sons who were killed in the war were old grocery bills, laundry bills, all sorts of worthless scraps.’

‘I was delighted to hear that Ray Lawler is turning 100 years old – I wish him a very happy birthday and many happy returns. I remember going with my parents when I was about 12 to see Summer of the Seventeenth Doll with Ray as Barney and Noel Ferrier as Roo and absolutely loved it. I think this experience started my love of live theatre. I have seen the trilogy a number of times and still love this story and the characters who are so real.’ – Lilli Klein, theatregoer

Of course, he’s using the word ‘pathetic’ in a way few Australians do today. Words change. Many of the lines that The Doll’s original audience would have found familiar are lost on younger readers today.

Places change, too. In a beautifully lyrical line, the late playwright Michael Gurr describes his sometimes mentor Lawler returning to his childhood home: ‘He writes about walking down the street he grew up in, finding the place unrecognisable, so going back to the top of the street and walking it with his eyes on his feet. His feet will remember.’

In a sense, Lawler himself was lost to Australia after The Doll. The unprecedented international success of the play left its writer with an equally unprecedented burden: the Australian tax office had never had to grapple with the international success of a local playwright, because there hadn’t been one. The ensuing confusions meant the playwright who put Australia on the map was forced to live in a kind of tax exile in Denmark, England and Ireland.

Valerie Bader, Steve Bisley, Genevieve Picot and Frankie J Holden in MTC's 1995 production of The Doll, directed by Robyn Nevin

Photo: Jeff Busby

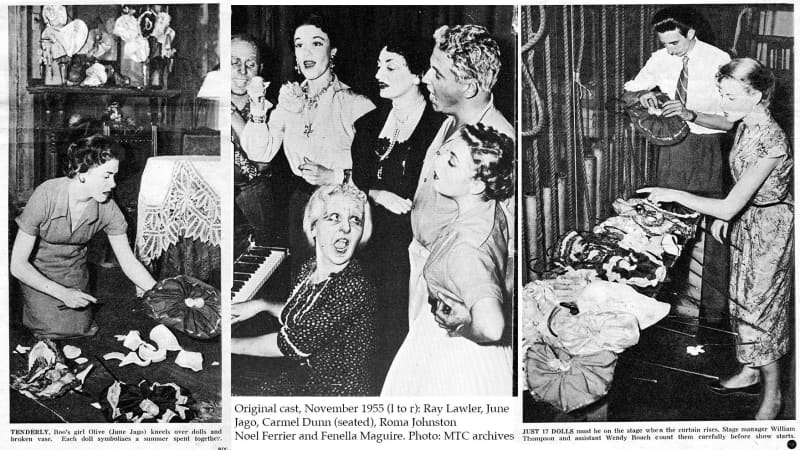

Press clippings and photos of Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, 1955

Image: MTC archives

Bruce Myles, Sandy Gore and Peter Curtin in MTC's 1975 production of Ray Lawler's Kid Stakes, directed by John Sumner

Photo: David Parker

Bruce Myles, Sandy Gore, Carol Skinner and Christine Amor in MTC's 1976 production of Ray Lawler's Other Times, directed by John Sumner

Photo: David Parker

Rona McLeod and Gabrielle Hartley in MTC's 1981 production of The Truce, directed by Ray Lawler

Photo: David ParkerHis 1963 play The Unshaven Cheek opened the Edinburgh Festival in 1963 (it features an illiterate mother). And he returned to what he called ‘the Doll people’ on two more occasions, with prequels Kid Stakes (1975) and Other Times (1976). This was after he had at last returned to Australia to take up a role as associate director of the Melbourne Theatre Company, the same company that had evolved from the Union Theatre Repertory Company.

Though an accomplished actor and writer, he has rarely pursued publicity. It’s hard to overlook his legacy, however, and the conversation he began goes on today, as more and more voices join in. In a way, they’re all Doll People, and as of 23 May this year Lawler, a Victorian, born in Footscray, is 100. He has written a few other plays.

Published on 21 May 2021