According to renowned horror author Stephen King – writing in his nonfiction survey of the genre, Danse Macabre – Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw is one of ‘only two great novels of the supernatural in the last hundred years’. The other is Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. Given King’s own output, that’s a bold statement.

James’s iconic ghost story centres on an unnamed governess who takes a job at Bly, the country estate where her new employer’s niece and nephew live following the death of their parents. Life at Bly with the children seems idyllic at first, but the governess grows increasingly worried for the safety of her charges when she begins to see the spectral figures of two former employees, Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, haunting the grounds.

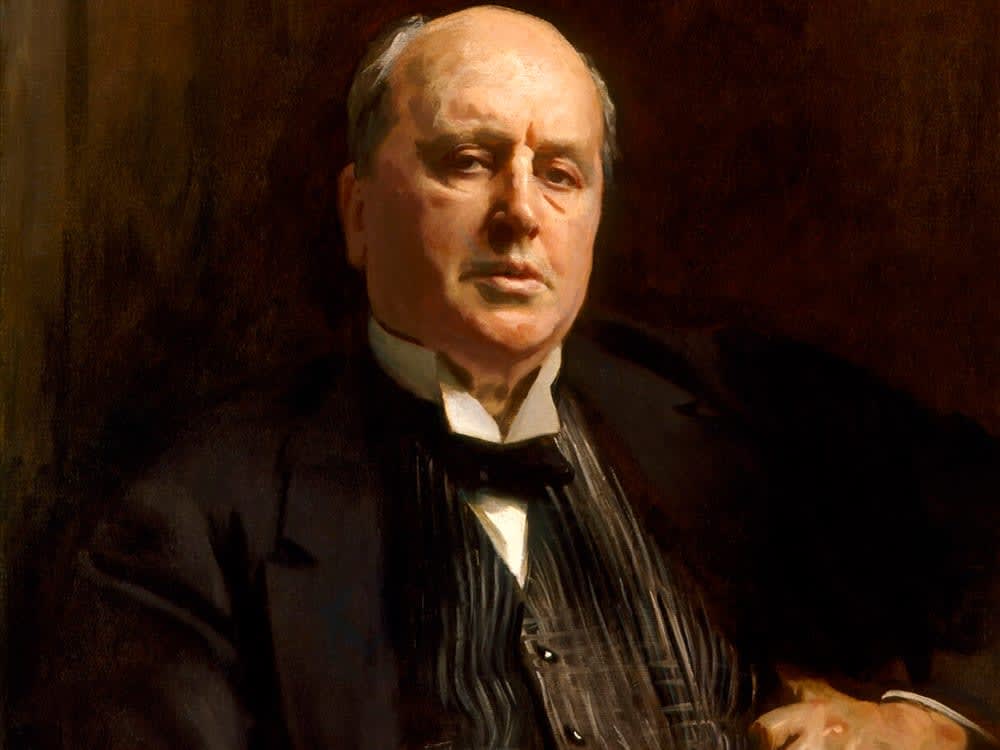

The New York-born James is today widely recognised as one of the great English language novelists. Thrice nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, his best-known novels include The Bostonians, The Europeans, The Portrait of a Lady, Washington Square, The Golden Bowl and What Maisie Knew – all of which have been adapted for the screen. He also produced a vast oeuvre of short stories and novellas, including many acclaimed ghost stories.

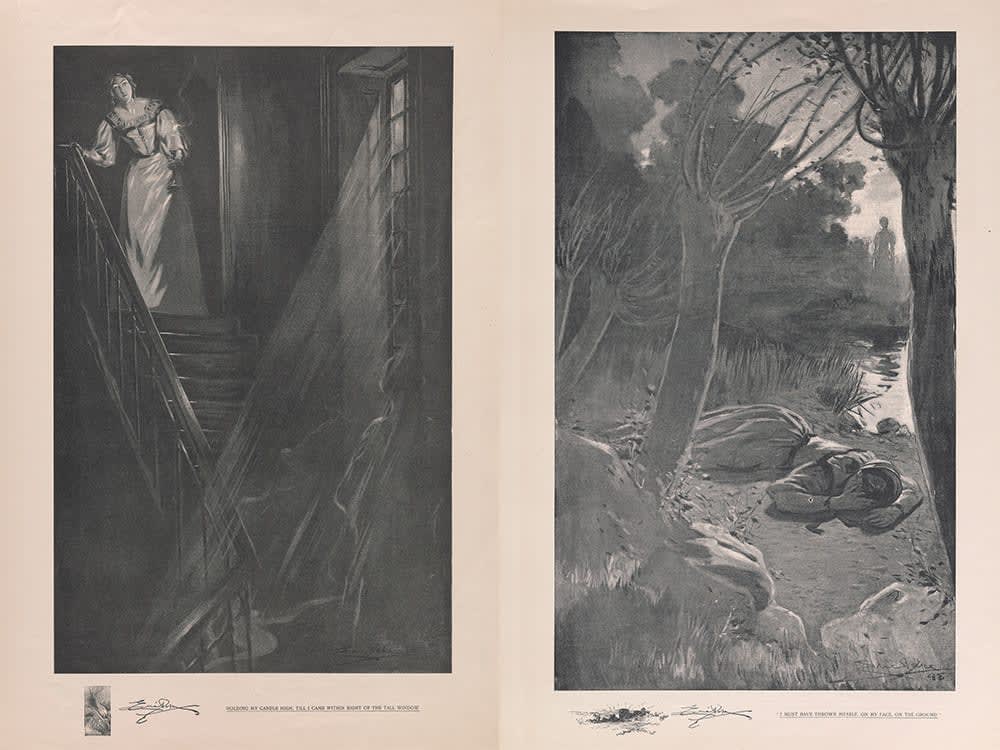

Of these, The Turn of the Screw is by far the most famous, as well as being the most analysed and most adapted of all James’s writings. First published in 1898 in Collier’s Weekly, this humble volume has inspired endless critical debate and numerous adaptations in other media, from film and television to stage and opera. Its cultural impact has been vast, and its influence on the genre immeasurable.

Portrait of Henry James painted by John Singer Sargent. Source: National Portrait Gallery, London

A Critical Hit

Part of ongoing fascination with, and love for, the novella is due to its inscrutable ambiguity: is it a ghost story or a psychoanalytic portrait of mental illness? Like the Mona Lisa of literature, it refuses to give up its secrets one way or the other. Academic debate on the matter has raged for over 100 years, but the mystery is no closer to being settled.

Writing in Vanity Fair, K Austin Collins notes that the story’s ‘sly manipulation of truth, illusion, and subtext inspired an entire critical and literary discourse predicated in part on whether these ghostly phenomena were “real” or a figment of the governess’s hyperactive imagination’. Those who read it as a straightforward tale of the supernatural, known as apparitionists, argue that James himself described it as a ghost story. An apparitionist reading might therefore interpret The Turn of the Screw as an allegory about good and evil. On the opposing side are the non-apparitionists, who view the governess as an unreliable narrator, plagued by hallucination. Led by literary critic Edmund Wilson, who declared the governess ‘a neurotic case of sex repression’, this camp frequently holds that the book is a Freudian study in psychopathology.

There’s also a middle ground, a kind of literary no man’s land of shifting sands and shades of grey. Writing in The New Yorker, Brad Leithauser sums it up neatly, arguing that ‘The Turn of the Screw is greater than either of these interpretations. Its profoundest pleasure lies in the beautifully fussed over way in which James refuses to come down on either side. In its twenty-four brief chapters, the book becomes a modest monument to the bold pursuit of ambiguity. It is rigorously committed to lack of commitment. At each rereading, you have to marvel anew at how adroitly and painstakingly James plays both sides.’

Illustrations, by Eric Pape, for The Turn of the Screw in Collier’s Weekly, March–April 1898.

Adapt and influence

This fluidity has given other artists a century of leeway to interpret, reimagine and adapt the work, across multiple mediums and around the globe. Benjamin Britten turned the story into an opera. William Archibald’s play The Innocents, which debuted on Broadway, is Turn of the Screw in all but name. Truman Capote adapted Archibald’s script into a screenplay for a widely praised 1961 film starring Deborah Kerr and Michael Redgrave.

Screen adaptations of the book are many and varied, including versions in Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, German and French. Rusty Lemorande set his version in the swinging 60s, with Marianne Faithful narrating. For the BBC, Tim Fywell chose a WWI-era asylum, with a cast that included Downton Abbey’s Michelle Dockery and Dan Stevens. Premiering at the Los Angeles Film Festival in January this year, Flora Sigismondi’s The Turning brings the story into the mid-1990s.

Ingrid Bergman, Lynn Redgrave, Patsy Kensit, Johdi May and Leelee Sobieski have played the governess onscreen. Marlon Brando starred as a still-alive Peter Quint in a prequel, The Nightcomers. Nicole Kidman’s 2001 film The Others isn’t a direct adaption but it clearly shares the same DNA.

Due for release this year is Netflix series The Haunting of Bly Manor. Produced as a follow-up to the streamer’s acclaimed adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, it’s almost an inversion of James’s influence on Jackson.

The Haunting of Hill House. Image: Netflix

Shirley Jackson

Born the year James died, Jackson was an equally prolific and talented writer. She was also heavily influenced by him – down to the ‘Jamesian rhythms in her sentences,’ in the words of Joyce Carol Oates. The Haunting of Hill House is arguably her best-known novel, and is routinely described as one of the greatest ghost stories ever written. Her other books are also highly praised, from The Lottery – one of the most famous short stories in American literature, and sometimes referred to as the original Hunger Games – to the masterful We Have Always Lived in the Castle, an unsettling and macabre tale of paranoia and social isolation that takes on new resonance for readers in these unsettling and macabre times.

Despite her obvious literary achievements, Jackson was rarely taken seriously during her short life (she died in 1965, aged just 48). Derogatively nicknamed Virginia Werewolf thanks to her personal and professional interest in the occult, she grappled internally with anxiety, depression and drug abuse, and externally with a dysfunctional, unhappy marriage and rampant sexism. Her acute sense of otherness and alienation is manifested as an ongoing theme in her oeuvre, and is part of what makes her writing so chillingly effective.

Since her death, however, Jackson’s reputation and recognition has only grown. This year she is the subject a new biopic, playing at select cinemas now and when they re-open. Simply called Shirley, it stars Elisabeth Moss as the reclusive author in what has been described as an Oscar-worthy performance. The movie, which won a special jury award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, doesn’t pretend to be an entirely accurate account of its subject’s life, instead opting to instil a similarly gothic sense of tension and dread in audiences as Jackson’s own work did.

Elisabeth Moss in Shirley. Image: Madman Entertainment

Houses aren’t haunted; people are

Like James’s governess, Jackson’s protagonists are almost always unreliable narrators, Hill House’s Eleanor Vance especially. Both The Turn of the Screw and The Haunting of Hill House situate the reader inside their heroine’s unravelling mind and leave us equally uncertain. And while James was the one who established subtlety and ambiguity as cornerstones of the psychological ghost genre, writer Joe Hill (aka Stephen King’s son) describes Jackson as the first author to truly understand ‘that houses aren’t haunted; people are’. Both James and Jackson knew there is nothing more frightening ‘than being betrayed by your own senses and psyche’.

The deliberate ambivalence and quiet dread that made The Turn of the Screw such a significant literary creation is also what makes it an evergreen inspiration, built upon and carried further by Jackson and a long line of authors after her.

Published on 30 July 2020