Elizabeth Gadsby discusses designing a world that moves between the conscious and unconscious and how small details can go a long way.

What were your first impressions after reading the script and what immediately jumped out for you in terms of design?

It’s such a text-based and interior piece and, in a way, you don't need to stage it. The text creates this internal world that you can sit in. It's almost like reading a novel where you go through layers of character and there's enough image-making in the text itself to create those images in your mind. So it's one of those really delicate pieces where the design can't be too heavy-handed otherwise it will swamp the text and structure of the play.

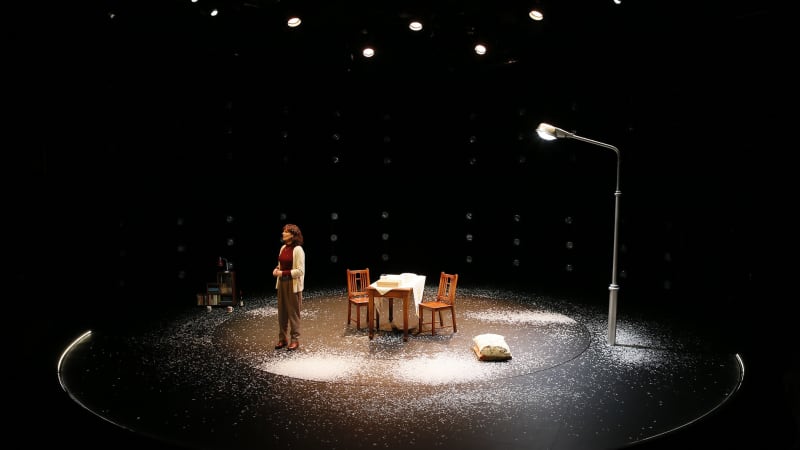

I really responded to the image that the play builds toward, that of an impression of a body in the snow. It reminded me of the performance works by Ana Mendieta. She did a lot of body-based work that would leave impressions in the landscape or impressions in an environment. That particular image resonated with me because the work feels like this accumulation of experience that makes an impression on someone’s psyche. Even when they move on with their life or past a certain point, the experience still resonates and has this kind of echo to it. They are memories you carry around within yourself and they rear their head again and again, at different points in time.

How do you reconcile with the interior and delicate nature of this play when designing the set?

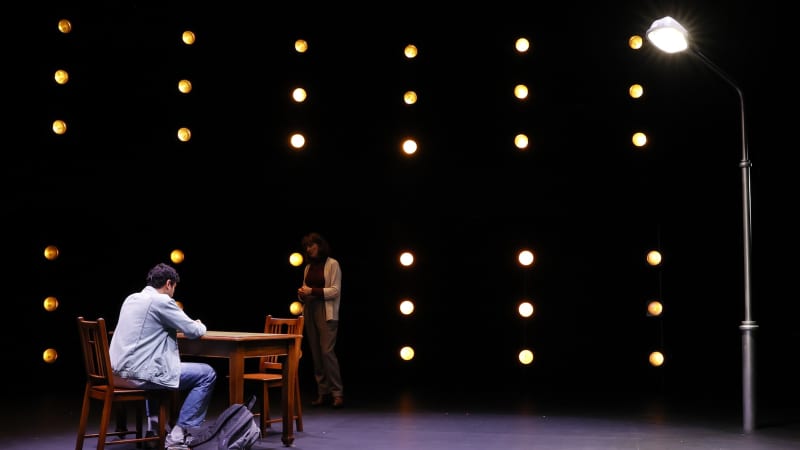

To a certain extent, some of the scenes are quite naturalistic. So even though we’re sliding through different layers of storytelling there are moments that feel very grounded in naturalism – for instance, sitting in an office or a lounge room – that do need certain objects to give them grounding in the space. But we knew that there should be enough space around those things, so that the characters can step in and out of the solid moments and into the more slippery ones.

Can you expand a little more about how you evoke the sense of Bella’s internal world in the set design?

We discussed image making that was more psychological than naturalistic. For example the snow fall. When you have snow falling on indoor objects, it signifies to the audience that they are not in a naturalistic space anymore. That the snow isn’t snow, it’s something more psychological, echoing the character.

There are two moments where it feels like Bella is going through a tunnel and she describes going down into a kind of cosy softness. In these moments, the substance of snow and the way that it fills the space evokes this by closing everything in.

How do you collaborate with Director Sarah Goodes on the set design and concept for this play?

When Sarah and I work together we talk around the ideas of the work a lot before we settle on anything physical. Sarah always starts with a feeling – a feeling she wants to create for a particular character and the specific feeling that she wants an audience to tap into. And they are often small and quiet. I think primarily she’s really interested in psychology and self-knowledge. So when we’re developing a work, our conversations are not often about big gestures, it’s really about what can we do to get the quiet, small moments – where something in a character shifts or drops – to really sing.

Sarah is always thinking about small details and in a way that helps us create the guiding design principles for the work. For example, at one point we were talking about if we want to leave props and objects on stage, or do we try and get them off stage. On one hand, there’s a practical concern, because it is clunky getting stuff on and off stage and the less we can do the better. But it is also a dramaturgical decision. We felt that the things that remained on stage support the emotional heart of the work. They are symbols of possible connection between the two characters. It’s like each object becomes a little beacon, or a little reminder, of either the moment that could have been or one that did actually occur. Those objects can revolve past them even though it’s not happening in the present moment. It also allows the audience to compile an image in a nonlinear way, the way that memory works. You don’t often remember things in a logical, linear manner. It’s a series of images or experiences or sounds that start to sit on top of one another.

You mentioned that the objects sometimes revolve past the characters. Can you talk a little bit more about how the revolve works within the play?

The revolve allows us to create a force in the show that exists outside of the characters; that there are certain things beyond their control. It was partly to do with the character of Christopher. We wanted the ability for him and Bella to move away from one another, or toward one another, without having to physically walk through the space. It’s almost like they’re these little atoms that are being drawn apart and together again. And what we really liked about the revolve was, again, it places us in a space where these characters can be both naturalistic and then also feel more like an idea or a memory because they can float away in a non-naturalistic way. It allows the same thing with the prop elements in the space. We have the ability to move things through space to come together to create an image then move them apart again. So having that mechanism really helps to create the rhythm in the text, where you’re in something for one moment, and it’s very present and naturalistic, and then that moment passes and you slide into another train of thought.

The Sound Inside is on stage until 2 July at Arts Centre Melbourne, Fairfax Studio.

Published on 27 May 2022