Fact checking, as it’s understood by the characters in The The Lifespan of a Fact, has existed for less than 100 years. It began in the era of yellow journalism, when it was a job for women only; it languished as the internet took off and simultaneously annihilated the newspaper business model; and it exploded again with the rise of the 21st century’s version of yellow journalism: fake news.

Writing in the Columbia Journalism Review in 2019, Colin Dickey recounts the tale of a mid-century Egyptian fact checker whose dedication to his job landed him in jail[1]. As the story goes, the hapless fellow ran afoul of the authorities when he attempted to measure a palace wall in person, in order to confirm its height. As Dickey states, this level of above-and-beyond commitment reveals the great truth of fact-checking: it’s sometimes more work than it’s worth.

The story may or may not be true but it has shades of a major plot point in The Lifespan of a Fact – which our fact checking reveals did not actually happen: ‘I did not put my liberty at risk to check anything,’ says the real Jim Fingal, who nevertheless spent several months fact checking a non-fiction essay he knew was not intended to be strictly correct. In the 21st century of fake news, alternate truths and Facebook stooges deliberately distorting information for political or financial gain, it’s difficult to imagine such devotion to over-delivering in the name of accuracy.

Rehearsal photo of Nadine Garner as editor Emily Penrose, grappling with the facts. Photo: Charlie Kinross

Ladies first

The first fact checkers were women who were given free rein to question, challenge and stand up to their all-male writing and editing colleagues[2] – a rarity in the 1920s, when TIME magazine is generally acknowledged to have initiated the profession as we understand it. Reflecting on her tenure as the first person officially employed by TIME as a fact-checker (or researcher, as it was initially called), Nancy Ford told a historian that the best part of the job ‘was that you could say what you thought and didn’t have to be respectful’.

And although few fact checkers (that we know of) went as far as the diligent Egyptian, the job was traditionally considered difficult and demanding. It seems to have been uncommon for fact checkers to last more than a few years in the role, seemingly worn down by the long hours and ‘grisly’, ‘unpleasant’[3] work (although it’s probably just as likely that many left when they wed, as it wasn’t until 1964 that the US outlawed ‘marriage bars’ for working women; 1966 in Australia[4]).

‘I just fact checked a f***ing article! Nothing I do today will be harder than that.’ – Daniel Radcliffe

At TIME, the challenges of the work would be compounded by weekly error reports that ‘detailed the mistakes made, excoriating the (lower-paid) woman doing the checking rather than the male writer on the piece’[5]. TIME’s own history of fact checking wryly notes that following a 1971 ruling on sex segregation at work, the magazine finally allowed men to do the job, ‘and by 1973 [they] had managed to hire and keep four men’[6] in the role!

More recently, Daniel Radcliffe spent a mere day fact checking at The New Yorker as part of his research to play Jim Fingal in the Broadway premiere of The Lifespan of a Fact. At the end of that day, he apparently exclaimed ‘I just fact checked a f***ing article! Nothing I do today will be harder than that.’[7]

Ipso facto

The quest for accuracy existed prior to the 1920s, of course, with the editorial embrace of the subject beginning to appear in the 1800s, but with responsibility left to the editor or the reporter. But the increasing popularity of yellow journalism during the early years of the 20th century brought with it a desire for stronger standards or processes. Joseph Pulitzer’s son Ralph established the Bureau of Accuracy and Fair Play at the New York World in 1913 ‘to assure his readers they could believe what they read’[8] but it worked retroactively, identifying already published errors and inaccuracies. It wasn’t until TIME hired Nancy Ford in 1923 for their research department that fact checking became proactive, aiming to prevent errors and inaccuracies from making it to print in the first place[9].

TIME’s revolution established a trend, with other publications quickly following suit, and fact checking became standard at respected news organisations throughout the 20th century. But the advent of the internet, and the massive disruptions it caused to global journalism, saw newsroom budgets progressively gutted and fact checkers were often the first to go. As social media took over, so did misinformation. The 2016 election of Donald Trump ushered in a post-truth world that seemed to toll a death knell for verifiable facts.

‘Much like Santa Claus and unicorns, facts don’t actually exist!’ – Julia Shaw

Of course, this is objectively not true. And quietly, in the background, the business of fact checking continued, and began to change. And then to boom. In 2014, the Duke University Reporter’s Lab counted 44 dedicated fact-checking organisations globally; by 2020, the number had topped 300. But the fact checking these organisations practise is specific, targeted and – as in the early days – the checking comes after the fact, so to speak. It is the independent (usually) work of verifying and correcting spin or falsehoods that have already been published, broadcast or aired, typically for political, ideological or financial gain.

Spearheading this new era were websites such as Snopes (which launched in 1994 and initially focused on busting myths and urban legends), FactCheck.org (2003) and PolitiFact (2007). Today, these and many others – including the RMIT ABC Fact Check – are all signatories to the code of principles established by the International Fact Checking Network, a Poynter Institute initiative designed to promote best practice and standards. Facebook even started working with the IFCN, though its commitment to the principles never quite stuck.

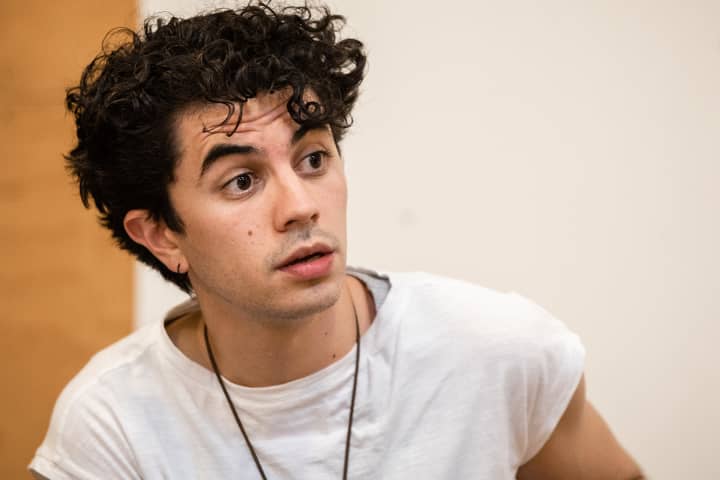

Steve Mouzakis and Karl Richmond rehearsing The Lifespan of a Fact. Photo: Charlie Kinross

A fact is a fact (except when it’s not)

While a commitment to factual accuracy is both commendable and necessary, sometimes the truth is not so black and white. In a 2020 Scientific American article on the psychology of fact checking, Stephen J Ceci and Wendy M Williams note that any individual fact checker’s personal or political biases can influence what they confirm as genuine, and what they even deem worthy of checking in the first place. ‘Laboratory studies reveal that, when shown a video of a group of protesters, people see either a peaceful protest or an unruly mob blocking pedestrian access, depending on their sociopolitical beliefs,’[10] they write, pointing out that these results are replicated in real-world situations.

Also writing in Scientific American, Julia Shaw goes even further, stating ‘much like Santa Claus and unicorns, facts don’t actually exist.’[11] Shaw is being deliberately provocative, of course: her article is about the scientific method of testing a hypothesis again and again until a theory is established. But a theory still isn’t fact. ‘Knowledge is like Schrödinger’s cat,’ she argues. ‘Simultaneously reality and delusion. Truth and lie.’

This is the position presented by The Lifespan of a Fact, but framed through an artistic lens instead of a scientific one. Essayist John D’Agata is not interested in scientific accuracy, but in poetic truth; he wrote to his subject’s ‘spirit, not his body’. Fact checker Jim Fingal, meanwhile, believes that even the most minor misrepresentation of verifiable, objective data undermines society’s trust in itself. Their back and forth is a negotiation over the ontological nature of truth. And that’s a fact![12]

The Lifespan of a Fact runs from 15 May at Arts Centre Melbourne, Fairfax Studio. Tickets on sale now.

[1] Dickey, Colin, ‘The Rise and Fall of Facts’, Columbia Journalism Review, Fall 2019

[2] Fabry, Merrill, ‘Here’s how the first fact checkers were able to do their job before the internet’, TIME magazine, 24 August 2017

[3] Friedman, Sande & Schwartz, Lois C, No Experience Necessary: A Guide to Employment for the Female Liberal Arts Graduate, Dell Publishing Co, 1971

[4] Sawer, Marian, The Long, Slow Demise of the Marriage Bar, Inside Story, December 2016

[5] Ibid, TIME magazine

[6] Ibid, TIME magazine (emphasis ours)

[7] Schulman, Michael, ‘Daniel Radcliffe and the Art of the Fact-Check’, The New Yorker, 8 October 2018

[8] Kovach, Bill & Rosenstiel, Tom, The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and What the Public Should Expect (3rd edition), Penguin Random House, 2014

[9] Interestingly, TIME’s founders had originally considered calling their new magazine FACT

[10] Ceci, Stephen J & Williams, Wendy M, ‘The Psychology of Fact-Checking’, Scientific American, 25 October 2020

[11] Shaw, Julia, ‘I’m a Scientist, and I Don’t believe in Facts’, Scientific American, 16 December 2016

[12] Subject to interpretation. Individual results may vary.

Published on 12 May 2021