The 1950s carry an awful lot of cultural baggage for one decade. Political conservatives wax nostalgic for this golden period, pointing out its post-war optimism, suburban middle-class prosperity and technological innovation. Meanwhile, progressives demonise the 1950s as a philistine monoculture, arguing that this was a terrible time to be anyone other than a straight white man. Politicians are frequently criticised for policies that “take us back to the ’50s”.

But in Laura Wade’s satirical play Home, I’m Darling, that’s exactly where one 21st-century housewife longs to be. Judy has decided to emulate a 1950s lifestyle, but finds her fantasy challenged by skeptical friends and family. ‘The ’50s didn’t even look like this in the ’50s,' says Judy’s mum, Sylvia. ‘You’re living a cartoon. Being nostalgic when you weren’t even there…’

Nikki Shiels (Judy) in rehearsal. Photo: Pia Johnson

THE REAL 1950s

In Britain, where Wade’s play takes place, the decade Sylvia remembers was a dynamic period of change and uncertainty. The still-recent horrors of World War II had shaken people’s trust in traditional morality and authority, as well as their faith that their lives mattered. Rationing was still in effect, and the Empire was crumbling.

In Australia, Robert Menzies was Liberal prime minister from 1949 to 1966. Popular memory enshrines a contented white-collar milieu of breadwinning husbands in suits, and their perfectly groomed wives. But the spectres of communism and nuclear danger also haunted Cold War Australia, and the nation began to pivot from its traditional loyalty to Britain towards a new alliance with the United States. And postwar prosperity didn’t reach everyone.

‘For most working-class people, the decade is better remembered for its insecurities and fears,’ writes historian Mark Peel. ‘Theirs was a different kind of fifties. A public-housing, fibro and first-job-on-the-assembly-line fifties, a laminex-table, new-gas-stove and pigeons-out-the-back fifties…’

MAD MEN … AND WOMEN

These were Depression kids who’d grown up in rural or inner-city poverty, in families with too many mouths to feed. To borrow from Mad Men, the TV series that has become a touchstone for today’s fans of midcentury culture – including Judy in Home, I’m Darling – they were less like suave adman Don Draper, and more like Dick Whitman, the shameful self Don sought to escape and conceal.

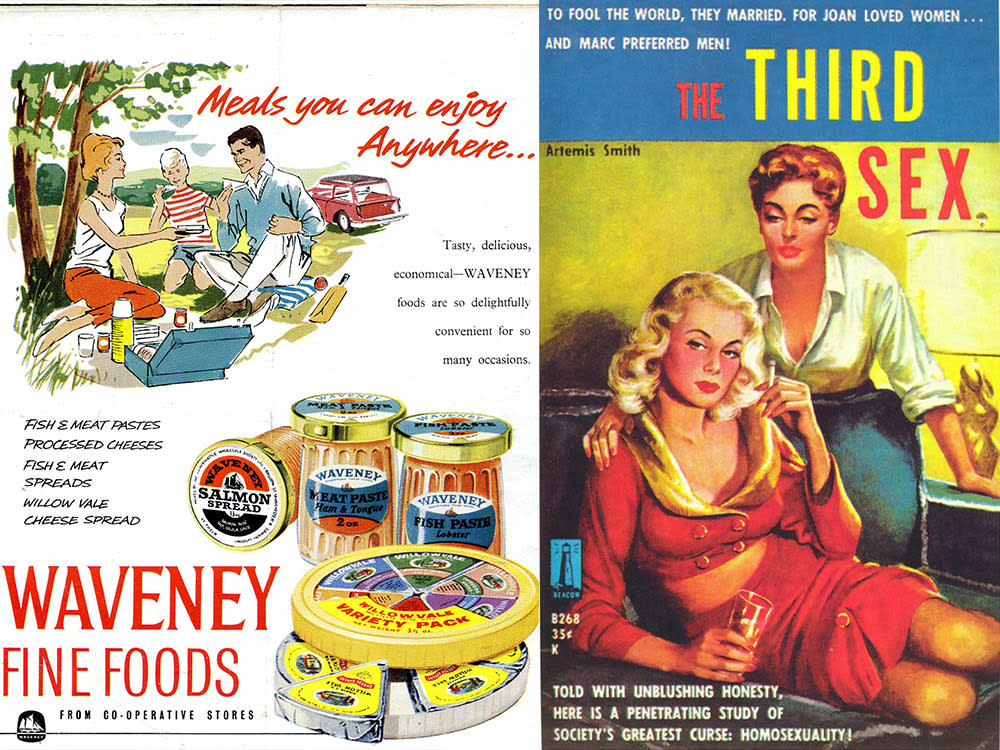

And many people struggled to fit into a world whose glossy consumerism they didn’t share. While advertising depicted suburban nuclear families enjoying the latest cars, holidays, processed foods, fashions and electrical appliances, 1950s pulp novels and movies told lurid tales of bikies, juvenile delinquents, same-sex lovers, beatnik junkies and “reefer madness” that were at least partly based on real-life subcultures and bohemian circles.

Waveney Fine Foods late 1950s advertisement

The Third Sex (1959) by Artemis Smith, who coined the term 'come out of the closet'

Meanwhile, modernist art, literature and design sought radical forms of expression that were intended to critique and confront. In 1953, British architect Alison Smithson used the term “New Brutalism” for the first time, sparking a utopian movement. Young, idealistic architects used cheap materials such as concrete to make modern homes affordable for everyone – not just rich people.

During wartime, home had been a space of both longing and contentment. But postwar pop culture teems with unhappy suburbanites. In George Johnston’s novel My Brother Jack (1964), the protagonist Davy Meredith wastes away in an unhappy Melbourne marriage. Connecticut couple April and Frank Wheeler make each other miserable in Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road (1961). And Grace Metalious’s 1956 novel Peyton Place – later a popular TV soap – unmasked small-town hypocrisy.

FEMINISIM & THE 50S?

‘I’m a feminist,’ Judy insists. ‘I get to choose now. This is what I’ve chosen.’

‘Wearing a frilly apron and dancing around with a duster isn’t feminist,’ Sylvia retorts: ‘if you look back long enough this was a man’s idea first.’

Other nascent second-wave feminists had the same suspicions as Sylvia. Women who had thrown themselves into the war effort were just getting used to the independence, responsibility and satisfaction of paid employment when they faced overwhelming social pressures to hand it back to returned servicemen.

Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and Mary McCarthy’s novel The Group gave voice to smart, educated ’50s women who were asking, ‘Is this all there is?’ And in Valley of the Dolls (1966), by Jacqueline Sussan, unhappy women popped barbiturates – the ‘mother’s little helpers’ that numbed a silent generation of housewives.

A 1950s housewife surrounded by cleaning utensils. Photo: Noske, J.D. / Nationaal Archief

THE NEW LOOK: 50s FASHION

Everyone knows the glamorous 1950s silhouette: long, full skirts floating on layers of crinoline petticoats under a nipped-in waist. This is Christian Dior’s 1947 New Look – which itself was a nostalgic homage to Dior’s Belle Époque childhood.

‘We were just emerging from a poverty-stricken, parsimonious era, obsessed with ration books and clothes coupons,’ Dior wrote in his autobiography. ‘It was only natural that my creations should take the form of a reaction against this dearth of imagination.’

Not everyone was eager to strap themselves up in waist-cinching girdles and hip padding, though. One controversial magazine photo showed older French women literally tearing a young fashionista’s clothes off. Meanwhile in the United States, protesters from the Little Below the Knee Club marched in public, holding up signs that read ‘Mr Dior, We Abhor Dresses to the Floor’ and ‘We Won’t Revert to Granma’s Skirt’.

Coco Chanel, whose simple, easy-to-wear designs had brought comfort into couture, simply scoffed, ‘Dior doesn’t dress women; he upholsters them!’

Dior's New Look on display in Stockholm, 1957. Photo: Gunnar Ekelund (Stockholm Transport Museum)

AT HOME WITH THE NEW LOOK

In public, perhaps, 1950s women looked glamorous. But in private, they struggled to meet the fashion and beauty expectations drilled into them by media, advertising and celebrity role models. British historian Sheila Hardy explains that housework was a hard slog, with few of the conveniences we now enjoy – from automatic appliances to late-night, seven-days-a-week shopping. (In postwar Liverpool, many housewives would drag a week’s worth of laundry to and from public wash-rooms.)

Susie Youssef and Nikki Shiels in rehearsals. Photo: Pia Johnson

‘They would have their husband’s evening meal ready but it was doubtful if they would have had time to run a comb through their hair, let alone wash their face and apply make-up,’ Hardy writes. They welcomed new synthetic fabrics that didn’t shrink in the wash like wool, need endless ironing like cotton and linen, or require dry-cleaning like silk.

And many real 1950s women eschewed heavily tailored and structured suits and frocks for simple, roomy housedresses with large and convenient patch pockets. One of the most popular was the Swirl, invented in 1944. The Swirl was essentially an apron dress: ‘Walk into it, button once, then wrap and tie!’ crowed advertisements targeted at time-poor housewives. By the end of the decade, brands such as Marimekko (founded in 1951) and Lilly Pulitzer (founded in 1958) had made loose-fitting shift dresses chic. They’d stopped being housewifely apparel and become fashionable resortwear.

TRUE TO LIFE?

Through her fashion and wider lifestyle choices, it’s clear Judy, like many vintage enthusiasts, genuinely feels a kinship with the 1950s; unlike most vintage enthusiasts, however, Judy’s appreciation is deeper than just wearing the clothing. But can we ever realistically re-enact the past? Or does the contemporary fantasy miss out on the complexity of its real political and social context? These are the kinds of questions Laura Wade poses to her audience in Home, I’m Darling.

Home, I'm Darling plays at Southbank Theatre from 20 January.

Published on 9 January 2020