In Neighbourhood Watch, we learn of Ana’s traumatic upbringing in Hungary before she emigrated to Australia. In this article from the Neighbourhood Watch programme, Paul Galloway looks at Hungary’s troubled recent past, and the reasons people like Ana fled to Australia.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Hungary stretched west to east from Bratislava to the steppes of Transylvania. It took in all of Slovakia to the north and most of Croatia in the south, including, Fiume (now Rijeka), its own port on the Adriatic. With its sister state Austria, it formed the duel monarchy of the Habsburg Empire, sprawled across the southern half of Europe. The country had run its own affairs from its own parliament in Budapest since the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, and, with no trade barriers across the empire and a bounty of resources under its control, Hungary enjoyed a fifty-year period of stability and economic growth that matched that of Germany, Britain and France. In 1914, Hungary had nothing to gain from going to war and a great deal to lose, though who could have predicted the decades of ruin that followed?

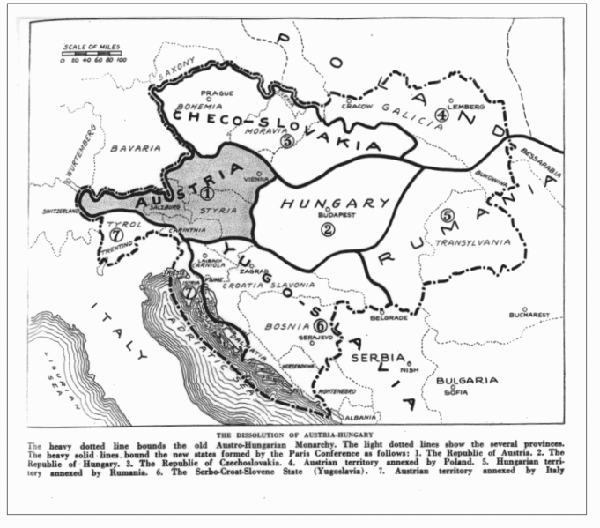

After the war came the carve-up and everybody took their slice. In the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost seventy per cent of its former territory. The new countries of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia claimed land in which Slovaks and Croatians were the majority; Romania expanded west into Transylvania. About a third of all Hungarians found themselves minorities in other countries. As new borders went up, Hungary lost contact with crucial mining resources, great tracts of agricultural land, its port and its major Austrian market. The economy collapsed.

Drafted borders of Austria-Hungary in the Treaty of Trianon and Saint Germain, published in The Independent, (New York), June 14, 1919. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Political instability inevitably followed: a shaky nationalist republic lasted a year before the communists under Béla Kun took over, whose Hungarian Soviet Republic lasted a mere five months before an ill advised attack on Romania backfired and the country was invaded by its neighbour. The Communist Army fled and, as the Romanians withdrew, Count Miklós Horthy filled the vacuum. In 1920, he was elected Regent in a constitutional monarchy that nevertheless gave him enormous power. His increasingly autocratic rule gave the country some stability over the next two decades – until war came again.

In June 1941, Hungary enthusiastically joined Germany in invading the Soviet Union and shared in the early success. But when fortune turned in the autumn of 1943 and Soviet forces pushed towards its Country borders, Hungary’s resolve began to waver. In Berlin, the German command feared that Horthy might do a deal with Stalin rather than see his country invaded, so they invaded Hungary themselves. The puppet government put in place in the spring of 1944, led by the Hungarian fascists of the Arrow Cross, had none of Horthy’s qualms about handing over Jews. By the end of summer, more than 400,000 Hungarians of Jewish descent were placed on cattle trucks for Auschwitz. Hundreds of thousands more Hungarians died in fighting off the Soviet invasion and perhaps just as many died in Soviet internment camps and in mopping up operations after the Soviets took control. The roads choked with refugees in advance of the Soviet lines.

Ten years as a Soviet satellite state brought a stagnant economy and widespread discontent that didn’t find expression until the autumn of 1956, when small acts of defiance in Budapest built into mass demonstrations for political freedoms throughout the country. After a predictably brutal response from the government, unarmed demonstration became armed insurrection and a revolution was underway. Then, as suddenly as it rose, the revolution was won. On 29 October 1956, the police and army went back to their barracks and the Soviet tanks left the city. Reformist Imre Nagy formed a government and promised democratic elections.

The new Hungary lasted a week. The Soviet army invaded on 1 November and it was all over a few days later. This crushing of hope after almost fifty years of diminution and repression was the final straw for many Hungarians. They abandoned their accursed country in vast numbers. Almost 200,000 Hungarians (2% of the population) crossed the Austrian border during the brief weeks it remained opened. After the border posts were sealed and mined, thousands more employed people-smugglers to lead them over the mountains. Twenty-eight countries offered asylum to the refugees – Australia was one.

Neighbourhood Watch is now playing at Southbank Theatre, the Sumner until 26 April.

This article is an excerpt from the production programme for Neighbourhood Watch, which is available for purchase at Southbank Theatre.

Published on 28 March 2014