Anne O’Hehir, Curator of Photography at National Gallery of Australia, shares her insights on the woman behind the lens – Diane Arbus.

‘She was the most seductive person I ever met in my life.’ This was the way that Anne Wilkes Tucker summarised the photographer Diane Arbus after meeting her as a young curator. Arbus’s ability to connect to the people she photographed is legendary and the images she made as a result of her interactions have an intensity and power that have rarely been matched. Fellow photographer Joel Meyerowitz characterised her as ‘an emissary from the world of feeling’. She cared, he believed, about the people she photographed; ‘they felt that and gave her their secret’.

Where did the intensity come from? An intensity combined with an almost frighteningly relentless ambition that she girded her loins with as she set out to build a career in the mid to late1960s. Such things are difficult to account for. Her biography does suggest some answers. Diane (pronounced Dee-anne) was born into wealth and privilege to Jewish second-generation New Yorkers in 1923. Her father David Nemerov ran a Fifth Avenue department store specialising mostly in women’s wear and furs. Alongside an older brother Howard and a younger sister, Renée, Arbus was brought up by nannies – her pre-occupied parents were emotionally absent: her father at work, her at times depressed mother more concerned with position and appearance. She attended the progressive, private schools of the Ethical Culture movement. Her school assignments are remarkable; the work of a student who is precocious, highly intelligent, an original thinker and widely read. There is an early interest in myth and archetypes which would remain throughout her life.

She married her childhood sweetheart Allan Arbus at eighteen and had two daughters, Doon and Amy. The young couple set up a photography fashion studio on Allan’s return from war – it was middling successful, their work competent though not greatly original or inspiring. They got assignments for magazines like Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Seventeen – but by the mid-50s Diane was finding both the business and the marriage stifling – she left both to find her own way.

Mostly self-taught, Arbus took a number of classes. Those with Austrian émigré photographer Lisette Model provided a breakthrough. Model encouraged her students to shoot only when they felt it in their gut and guided Arbus specifically to follow her instinct, to pursue her desire to photograph people on the edge of society. Her advice that the more specific a photograph was, the more general its message became, was also something that became a fundamental aspect of Arbus’s approach to her practice. She came to a distinctive style all her own, an edgy combination of classic, still compositions, working in black and white, that sit aside the deliberate use of a snapshot aesthetic where seemingly awkward moments and mistakes were used to give the images an immediacy and elements of surprising detail.

Arbus played an important role in the history of photographic practice as it developed throughout the twentieth century. She was part, certainly, of a wider movement towards a more private, psychological way of making pictures though in many ways her images seem to capture the anxieties and the frailties of a Cold War America in a way that few others could match.

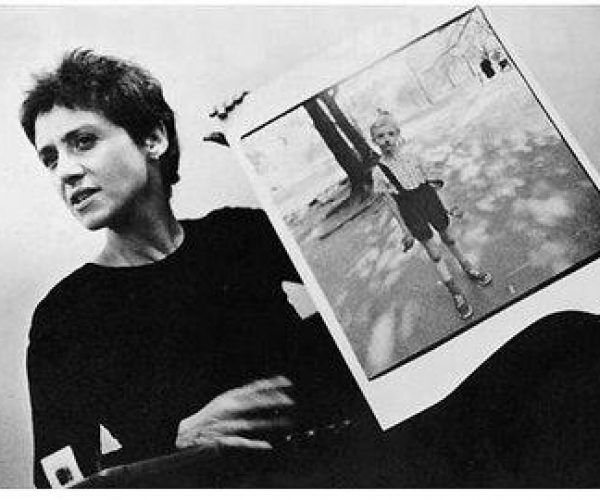

A photo of Diane Arbus presenting her photograph Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, New York, 1962.

Arbus’s curiosity about the world was insatiable – she felt she had been kept from it during her closeted childhood and set out with a vengeance to make up for lost time. She took off her clothes and joined nudist colonies, she frequented the seedy worlds of the ‘freak’ circuses, she went amongst the subcultures in the city’s parks. She stated at one point that there wasn’t anything she wouldn’t do to get a photograph. People who had suffered trauma – those born into physical disability for example, or those who didn’t fit in because of their sexual orientation or beliefs – fascinated Arbus. They lived, she felt, bigger lives than the rest of us, they were free in a way that we weren’t because they weren’t waiting for the axe to fall – for them it already had. They were, she believed, the real aristocrats. Living a true life, an authentic life mattered to Arbus, even or especially if it meant fighting for it – while acknowledging that self-knowledge and clear intentions, for herself, for everyone, are tricky. When Allan Arbus was asked later to sum up Diane’s greatest attribute in one word, the word he chose was courage.

People gave Arbus ‘their secret’, to use Meyerowitz’s turn of phrase, because she got in close and spent time. She intuited that people could only keep appearances up for so long – after that they would start to slip up – and it was then she believed that people revealed their true self (she had to shoot celebrities, for magazine assignments, but found it difficult at times – they were covered in shellac she believed, their practiced and polished ready-for-the-camera personas, difficult to get past). She was always on the lookout for the slippage – when you see someone on the street, she reflected, what you see is the flaw. She famously called this ‘the gap between intention and effect’. How we want to be seen rubbing up against how others see us.

The complexity of the photographic exchange was something that Arbus thought about long and hard and to which she brought her formidable intelligence. So often Arbus captures a moment of a real connection, of a great humanist empathy; you get the sense of the subject really staring back at Arbus, just as she was looking so intently and intensely at them – just as they now stare at us. Arbus moved to using a medium format camera in 1962 – this gives her work its distinctive square format and meant that she held the camera at waist level and so could remain visible to the sitter while the image was being made.

The emotional investment in her subjects, some of whom she knew for many years, sits alongside a dispassion, a toughness. There is cold distance in this; the camera is cruel, Arbus also said: the images themselves are never sentimental, never conventionally flattering. Meyerowitz may have felt she cared about the people she photographed but he also called her a ‘spider’, luring people into a soft and entangling and complicated transaction. These contradictions and complexities make the images Arbus produced in over little more than a decade, endlessly enigmatic, their meaning and intent still passionately debated today. They remain at their heart a mystery, a secret that will never be fully disclosed.

Anne O’Hehir is a Curator of Photography at National Gallery of Australia and curator of Diane Arbus: American portraits, National Gallery of Australia 3 June – 30 October 2016 and travelling.

Arbus & West plays at Arts Centre Melbourne, Fairfax Studio from 22 February to 30 March.

Published on 4 September 2018