When Mary Shepherd commandeered Alan Bennett’s Camden driveway, an unlikely 15-year friendship ensued.

When the real life Miss Mary Shepherd died in 1989, her author neighbour, Alan Bennett, set about writing a lengthy article for the London Review of Books to document the 15 years in which she commandeered his Camden driveway. It’s unlikely Bennett knew it at the time, but his diary entries over that decade and a half would end up forming the basis of a novel, a hit radio and stage play, and 16 years later, a feature film.

Bennett was raised by conservative, hard-working parents in Leeds, not long before the dawn of the Second World War. Despite the hardships of the day, he was a diligent student and worked methodically to win a scholarship to Exeter College at the University of Oxford, where he earned a history degree with first-class honours.

It was at the University in the late ‘50s that he befriended Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore while performing in the Oxford Revue. The foursome garnered instant fame at Edinburgh Fringe Festival with their revue show Beyond the Fringe, which they then toured to London and New York in 1960, setting all four young men up for illustrious careers in the performing arts.

Bennett’s first full-length play, Forty Years On, premiered at the Apollo Theatre in 1968, proceeded by a large body of radio, TV, stage and screen plays, as well as numerous short stories, novellas and a vast collection of non-fiction prose. Despite his self-proclaimed shyness, Bennett also continued to make appearances as a broadcaster and actor.

Of his many works, few have struck as deep a chord as his autobiographical texts. The Lady in the Van is a prime example of Bennett’s capacity to tap into the psyche of his own character, and the characters of those who circle around him. In the instance of The Lady in the Van, he splits his focus between his frail and elderly mother, and his belligerent, troglodyte tenant, Miss Shepherd.

Bennett writes himself into the play by incorporating both his literal self, ‘A. Bennett’, and his subconscious self, ‘A. Bennett 2’ or ‘The Writer’. These versions of Bennett represent starkly different aspects of his personality. Indeed, A. Bennett is critical of A. Bennett 2’s motivations to journalise Miss Shepherd at all. In the forward of his script Bennett notes, ‘the device of having two actors playing me isn’t just a bit of theatrical showing off and does, however crudely, correspond to the reality. There was one bit of me (often irritated and resentful) that had to deal with this unwelcome guest camped literally on my doorstep, but there was another bit of me that was amused by how cross this eccentric lodger made me and that took pleasure in Miss Shepherd’s absurdities and her outrageous demands.’

At the heart of Bennett and Shepherd’s real-life relationship, though, we find a message of tolerance and humanity; a melancholic reflection on Britain’s class system as it examines the cruel grip of poverty and the vicious spell mental illness can cast on society’s most forgotten inhabitants.

Like most writers, Bennett could see the wider story in the events unfolding around him. Writing Miss Shepherd’s narrative was effortless, he says, because of the vast amounts of material she provided him. However, finding the arc of his own character, and the journey he had been on in those 15 years, was much more challenging. As he explored the relationship between these two versions of himself, he discovered that A. Bennett 2, ‘The Writer’, became more exploitative in defiance to A. Bennett’s solicitousness: ‘In some sense the division between them illustrates Kafka’s remark that to write is to do the devil’s work.’ Though, write he did, despite consistently claiming it was never his intention to do so.

Looking back on this time in Camden Town, Bennett laments that he could have been more venturesome. Towards the play’s end, A. Bennett 2 reflects, ‘I learned there is no such thing as marking time, and that time marks you. In accommodating her and accommodating to her, I find twenty years of my life has gone.’ ‘The Writer’ admonishes his conscious self for skipping some of life’s great chances. He says, while he was busy caring for a ‘bigoted, blinkered, cantankerous, devious, unforgiving, self-centred, rank, rude, car-mad cow,’ others were journeying across Tibet or Patagonia, or engaging in salacious relationships.

Through the lens of Miss Shepherd, The Lady in the Van becomes an increasingly self-reflective and autobiographical play for Bennett. By looking at the moral implications and ethical complexities of telling someone else’s story, the writer ultimately peers into his own story and considers how one day it might be told.

The Lady in the Van plays at Arts Centre Melbourne from 2 February 2019.

Photo credits

Miss Mary Shepherd by Tom Miller

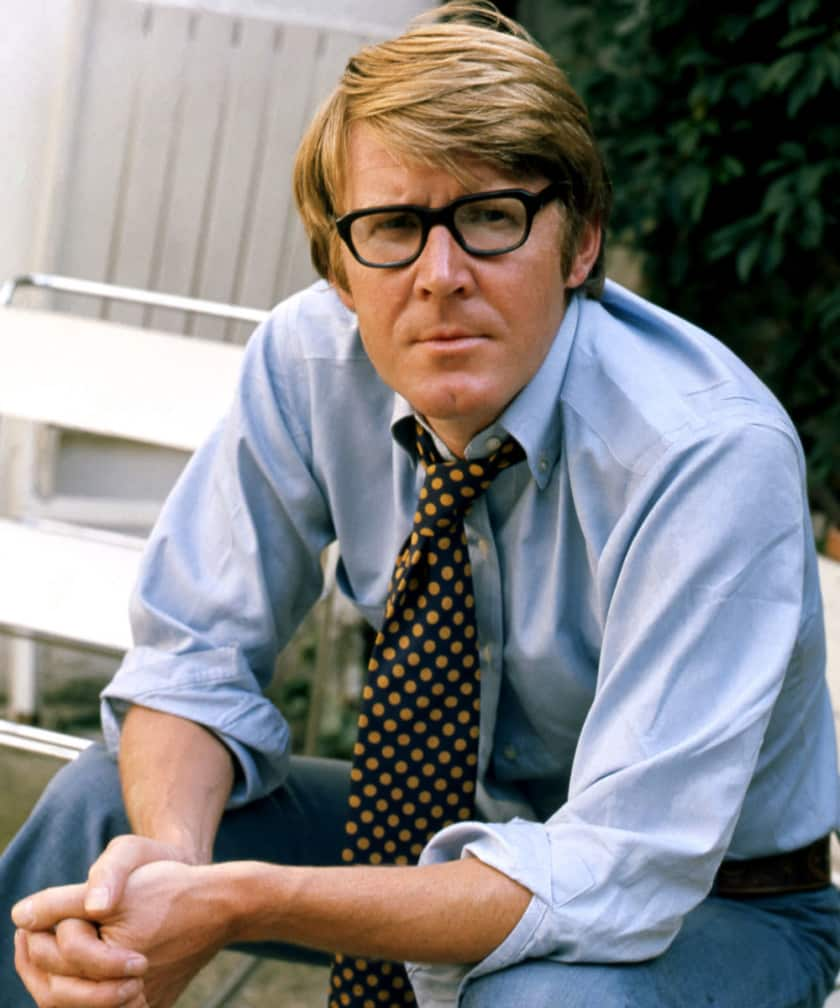

Alan Bennett by Allan Warren

Published on 30 January 2019