As we brace ourselves for the blockbuster solemnities of the Centenary of Gallipoli commemorations, it is fascinating and a little shocking to re-read Alan Seymour’s 1958 play The One Day of the Year, writes Paul Galloway.

Now that all the old World War One diggers are long dead and the World War Two diggers have thinned to a trickle, we can get away with idealising them as men and soldiers, abstracting them, as the TV advertisers are doing this week, into a single sanitised image of a tall, handsome man in pristine khaki and slouch hat standing solemnly at attention before a ghostly diorama of his comrades charging Over the Top. But back in the fifties those World War diggers were in their prime and larger than life, with as many scallywags as saints in their number. Thus they were hard to idealise, especially since their annual commemoration of their fallen comrades had become a chance to let loose. The jolt delivered by The One Day of the Year amidst all our current national chest-puffery comes from reading that fifty-five years ago Anzac Day was widely viewed as a national disgrace.

Back then, we learn from the play, Anzac Day followed an unvarying order of service: at dawn the ex-servicemen would gather around the cenotaph or memorial for the Last Post, to be followed by the stately march in ranks down the main avenue, then it was off to the pub for an afternoon of convivial reminiscence and toasts to the fallen, which inevitably declined into drunkenness, illegal gambling, public vomiting and fistfights. After the pubs closed at six, the old diggers would roll on home to face the ire, pity and fear of their wives and kids. In a later interview, Alan Seymour said that ‘this dichotomy, or connection, between the sombreness [of the service] and the Bacchanalian break-out fascinated me.’

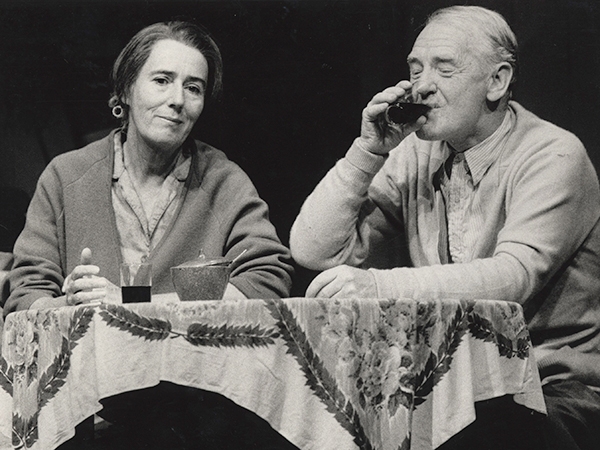

Wynn Roberts (Alf), Dennis Miller (Hughie), Elaine Cusick (Jan), and Bunney Brooke (Dot) in MTC’s 1961 production of The One Day of the Year.

It fascinated others, too. As a matter of course, most metropolitan newspapers editorialised on the brawls and drunkenness, but by far the most scathing attacks of Anzac Day in Sydney came from Honi Soit, the Sydney University student newspaper. Each year they would publish a mocking exposé of the old warriors, who were photographed passed out drunk in gutters or described throwing punches at anyone whose war service didn’t match up to theirs. At the time of an STC revival of the play in 2003, Richard Walsh, who edited Honi Soit in the early sixties, reminisced to the 7.30 Report upon the righteous rage of his younger self: ‘To us, as kind of young daredevils, [mocking the diggers’ behaviour] seemed like a tremendous piece of fun, so we basically decided every Anzac Day we would run an article … We did feel angry. We didn’t appreciate, in the way we do now, the sacrifices that they had made. I suppose because we were so furious at their inability to move forward, to see Australia in any positive way.’

Reading one such article in Honi Soit in 1957 gave Seymour the idea for his play set in the modest working-class house of the Cook family of Redfern. The father, Alf, who operates a lift in a building downtown, had fought in North Africa under Montgomery. He festers in his low status job, resents that the war robbed him of opportunities, and complains about the ‘poms’ and stuck-up nobs he has to serve. The only thing that gives his life meaning is Anzac Day, the one day of the year that he can feel good about himself. About this he falls into conflict with his son Hughie, now at university and working as a photographer for the student newspaper. The lad has had his head turned by his North Shore girlfriend, Jan, whose politics, we soon learn, are really no more than an extension of her of class snobbery. On the subject of Anzac Day, Alf’s combative wife, Dot, sits on the fence and gives both sides an earful. A fourth character, Alf’s mate Wacka, an old Gallipoli veteran, doesn’t say much until fairly late in the play when, in a moving monologue, he describes the confusion and horror of landing at Anzac Cove. It’s clear, reading it now, that the older characters commemorate a different Anzac Day to the one we commemorate today; less institutional and abstract, more personal and heartfelt. The stakes are high.

Maggie Blinco (Dot) and Edward Hepple (Wacka) in MTC’s 1986 production of The One Day of the Year

Alan Seymour, who died only last month aged 87, had a long career, mainly in Britain, writing for television. He also wrote ten plays, but The One Day of the Year made the splash. It also caused trouble from the start. A stuffy and patrician Adelaide Festival Board refused to put it on after it had won the festival’s play competition in 1958, and, during the first Sydney run, there was a bomb threat. The RSL hated it and waged a campaign against it that went as far as the Senate chamber, whence Seymour was described by one Senator as ‘a traitor and communist’. Yet, the general public loved the play, and it was a hit for the Union Theatre Repertory Company (precursor of MTC) when we staged it in 1961. Few took offence at the ignoble characterisation of veterans, since it was an accepted truth about the old rascals, and, anyway, drunkenness and authentic working-class language, especially when it was a bit blue, passed as good, edgy entertainment in those days. (The word ‘bloody’ explodes in Alf’s speeches with about the same frequency as ‘fuck’ does in the speech of a character in a play by David Mamet.)

Seymour was praised then, and rightly, for his ability to capture the speech of working-class Australians, but then he was working-class himself. Alf’s rants about ‘Australia for the Australians’ and his rails against the influx of ‘bloody Poms and I-ties’ were transcribed from Seymour’s memory of similar tirades by his alcoholic brother-in-law Alfred Cruthers, married to his eldest sister May, who, after Seymour’s parents died, took the nine year-old in. ‘He had all the same qualities [as Alf],’ Seymour said of Cruthers, ‘He resented his lack of education and was quite nasty about anyone that had a better deal than him.’ Yet, one of the strengths of the play is the way in which Seymour manages ultimately to build a sympathetic character out of Alf’s largely unsympathetic qualities. You feel sorry for the poor bugger. He’s a bloke thwarted by history and circumstance. Apart from his war service, the only thing he can take pride in is his son Hughie, studying economics at the big university.

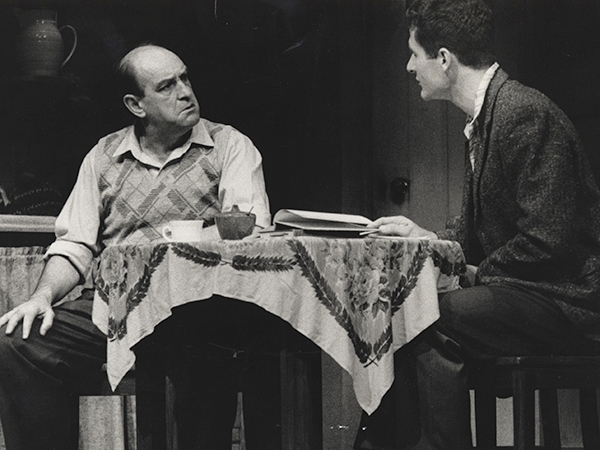

Peter Cummins (Alf) and William Brandt (Hughie) in MTC’s 1986 production of The One Day of the Year

The young people, Hughie and his girlfriend Jan, are the weaknesses of the play; that much was recognised even by enthusiastic early critics. In 1986, before an MTC revival, Seymour did his best to beef up Hughie’s part, to make him more his own person and less a good kid under the spell of Jan’s mixture of sex appeal and thoughtless rhetoric. (I cannot detail the changes because I couldn’t get my hands on the revised script. The rehearsal copy I found in our archives is from 1961. It was Wynn Roberts’s copy, who played Alf originally, with the actor’s mark-ups, line cuts and blocking notes scribbled throughout.) In superficial respects, The One Day of the Year belongs to the Angry Young Man genre, so popular in theatre and novels of the period, but Hughie is no Jimmy Porter. Just when the drama needs a good rebutting argument from Hughie, something forceful and true dipped in frustration and pain, the lad goes all tongue-tied and sentimental. Seymour never went to university, so, I suspect that, although he could imagine his way into Hughie feelings of inadequacy in being a working class boy making his way in the world of higher education, he couldn’t find its particular vocabulary to make it flow. As a comparison, read the relevant university chapters in Clive James’s Unreliable Memoirs, which captures the sound precisely and, of course, hilariously. But James, the university-educated son of a war widow from working-class Kogorah, had the advantage of direct experience to draw on. (Incidentally, James was Literary Editor of Honi Soit at the time other members of the editorial team were bagging drunken Anzacs.)

The One Day of the Year is not a great play, but it’s a great play of its time – and that, strangely, is its power for anyone coming to it now. Plays go out of date. This play certainly felt dated in 1986 when MTC revived it. Despite Seymour’s reworkings, it was received poorly by audiences and critics. It just didn’t seem relevant anymore, especially since Anzac Day was then in its doldrums with turnouts at the Dawn Service at historical lows. Yet at some time since then there must have been a point when the play moved from being out of date to being historical. That’s what it seems now. It nicely captures a moment of social history, the late fifties when children of the working class were just starting to take up places in universities, when vistas never allowed to the older generation were opened up for the younger. That was a seismic shift in Australian society and it is recorded here. Alf wants the best for his kid but can’t help feeling envious of his opportunities; Hughie feels caught between his stifling home-life and the larger world of ideas he’s found at uni. The drama works because the Anzac Day background seems less relevant now than the conflict between two characters who are really at war with themselves.

Published on 23 April 2015