Celebrating his 30 year anniversary with Melbourne Theatre Company, Richard Piper talks to Sarah Corridon about MTC in the 1980s, and what it means to be a gentleman of the theatre.

‘The porchlight, the torchlight, the frosted morning lawn, the cloak of daylight has finally been drawn on the tale of what the butler saw.’ Richard Piper’s first role at Melbourne Theatre Company was precisely thirty years ago in a 1987 production of What the Butler Saw. Since his professional theatre debut in Australia, Richard has gone on to appear in dozens of plays for the Company, in both ensemble parts and leading roles.

‘What’s happened to the time?’ he asks me curiously, before affirming that most people, in most industries, would probably feel a similar bewilderment when asked to reflect on the last three decades of their career.

When you spend your life in and out of costumes, characters and theatres all over the country (and world), 30 years is measured in productions, more so than years.

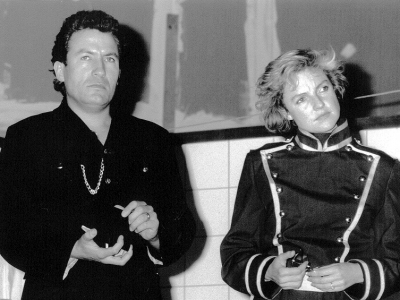

Richard spent the first part of his life in England, before travelling to Melbourne at the age of 32. His last five years on home soil were spent touring the UK in a successful, alternative rock-cabaret band called the Bouncing Czecks. ‘We had no money and no hits, and we behaved outrageously,’ he tells me.

Despite having all the sensibility of a rock and roll musician, theatre remained his first love. Upon arriving in Melbourne he met former MTC artistic directors Roger Hodgman and Simon Phillips, who welcomed him into Melbourne’s throw of theatre people in the 1980s. ‘I crash-landed into theatre and had the most amazing performers around me.’

‘The first play I did was with Shane Bourne, Judith McGrath and Bob Hornery. I was re-educated in the life of theatre.’

Richard credits Roger and Simon with keeping him in the country and reflects on his early days at MTC’s Russell Street Theatre as a halcyon time of life. What is now a derelict shell, once stood as the thumping heartbeat of Melbourne’s drama community, and became a home away from home for the English expatriate.

‘This was an extraordinary hub of activity – this tiny, grubby little theatre, where the stage door was down an alley,’ he says. ‘Theatre was incredibly spontaneous in those days. There wasn’t as much occupational health and safety.

‘For instance, in my first play, What the Butler Saw, Simon [Phillips] informed me quite soon after I started that I’d be pretty well naked except for a leopard skin dress and a policeman’s Helmut. [The play] involved me running down the centre aisle through to the Box Office. But the trouble was, once you got to the Box Office, you couldn’t get back to the dressing room by going through the theatre. So I had to go out onto the street in the leopard skin dress – and you can imagine Russell Street at that time of night on a Friday and Saturday – and run around to the stage door to get back in.’

‘I think everybody that worked there had an extraordinary bond to that theatre, because it was so mad and so wonderful and we were very closely aligned to the Duke of Wellington pub across the road.’

At that point in time, MTC operateed as a repertory theatre company. Meaning Richard and his peers could be rehearsing in as many as two plays throughout the day and performing in two at night.

‘We turned the dressing rooms into a pub, we literally lived in the building. I mean some people wouldn’t go home at night, they would just stay,’ he says. ‘Simon Phillips was certainly key in this empire of incredibly innovative art. We were a huge family making wild productions. It was fantastic. The Russell Street theatre was a very special little theatre for the Melbourne Theatre Company, right up until it closed.’

A list of Richard’s theatre credits spans many pages, with major productions for other leading theatre companies scattered between his appearances at MTC. Richard’s role in Sydney Theatre Company’s Gross und Klein and Belvoir’s The Wild Duck lead to tours through Europe, which took Richard back to his birthplace where it all began. Amoungst this substantial list, is it possible for Richard to pick favourites? I ask.

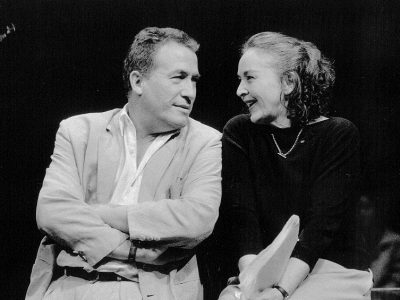

‘There are obviously – with all these plays – certain productions that come up and make you say, ‘Oh my goodness.’ Hannie Rayson’s Life after George was one of those plays where, for five or ten years after it closed, people would come up to me and say, ‘We saw that play.’ It was a life-changing Melbourne play. It was a very intellectual, highly charged and emotional production.’

Richard remembers there being a magic about Life after George, which he recalls Melbourne responding to accordingly.

‘There was a stage in the second half where the back of my neck went prickly and I thought, “We’ve done something to this audience.” And the standing ovation was extraordinary. At the end of it there was this enormous ‘vooosh’. And people went crazy. For more than just the play and the performance. It was more about what it did for Melbourne life and what it was saying about universities and the hope for young people.’

‘I guess that’s theatre at its most important, when people are changed by it.’

Richard admits it’s hard to know what to do after a performance of this nature. In the one-man show, directed by Simon Phillips, The Daylight Atheist, he considered the possibility of retiring. ‘Here I was for two hours playing a Belfast Irishman in New Zealand and it was the kind of experience where afterwards you take a deep breath and think, well I could retire…what else do you do?’ he asks. The role earned Richard a Green Room Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role.

I remind Richard of the often-gruelling rehearsal schedules that theatre calls for. The acute intensity of performing both matinees and evening performances late into the night. The endless picking up and putting down of a play in a new, unchartered city, where foreboding critics could rip his performance to shreds. Does he ever think of calling it a day and joining his spectators in the stalls? The answer is no. ‘It’s just too ingrained in me,’ he says. ‘When I get into a theatre, I feel I’m home. It gives you energy, so you give it energy.’

Richard is thankful to the band of older actors who welcomed him to Melbourne thirty years ago and acted as mentors in those early days. ‘They taught me how to behave in theatre and what superstitions to respect. To say goodnight when you leave the theatre, to thank stage management and, ultimately, to be a gentleman of the theatre, not just an actor.’

For Richard, the world of theatre is about having a laugh and welcoming people. ‘If I’m a mentor now, it’s about being careful, nurturing people, bringing them into a theatre company and making them feel welcome. And stories. Continuing the history. That’s something I really believe in. For over 150 years people have known this stuff. It’s worth not forgetting.’

Published on 20 September 2017