He was so widely regarded as Broadway’s Prince of Punchlines that when Neil Simon won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1991 for Lost in Yonkers, some thought a mistake had been made. However, the comedy writer’s unhappy childhood fuelled the themes of many of his plays, whose plentiful one-liners and gags belied their often dark and depressing subject matters.

Early life and career

Neil Simon was born in the Bronx in 1927, the second son of a textile salesman. The course of his early life – his upbringing in a struggling and unhappy Jewish family, his period of service in the Army Air Force Reserve in Mississippi, and his ambitions to become a comedy writer with his brother Danny – can be followed, albeit loosely, in his trilogy of autobiographical plays of the eighties, Brighton Beach Memoirs (1983), Biloxi Blues (1984) and Broadway Bound (1986). In the early fifties, the two Simon brothers worked their apprenticeship in comedy as revue writers in a summer holiday camp in the Poconos Mountains in Pennsylvania. That led to radio jobs and eventually staff positions on TV sketch shows and sit-coms. His 1993 play Laughter on the 23rd Floor recreates the aggressive camaraderie of the writers on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, which included other such young comic talents as Mel Brooks, Larry Gelbart and Carl Reiner.

Neil Simon was born in the Bronx in 1927, the second son of a textile salesman. The course of his early life – his upbringing in a struggling and unhappy Jewish family, his period of service in the Army Air Force Reserve in Mississippi, and his ambitions to become a comedy writer with his brother Danny – can be followed, albeit loosely, in his trilogy of autobiographical plays of the eighties, Brighton Beach Memoirs (1983), Biloxi Blues (1984) and Broadway Bound (1986). In the early fifties, the two Simon brothers worked their apprenticeship in comedy as revue writers in a summer holiday camp in the Poconos Mountains in Pennsylvania. That led to radio jobs and eventually staff positions on TV sketch shows and sit-coms. His 1993 play Laughter on the 23rd Floor recreates the aggressive camaraderie of the writers on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, which included other such young comic talents as Mel Brooks, Larry Gelbart and Carl Reiner.

Rise to fame on Broadway

He would have been happy writing for television indefinitely, but production was moving to California and Simon didn’t want to follow. Instead, he thought he’d try his hand at playwriting, although he didn’t know the first thing about it. With a lot of advice from producers and directors and by listening carefully to the response of out-of-town audiences, he hammered his first script through twenty-one complete drafts over three years until Come Blow Your Horn (1961) became a modest success on Broadway. His second play, Barefoot in the Park (1963), was an unambiguous smash and ran for 1,500 performances. What followed was the longest run of theatrical success in Broadway history, averaging a hit a year for more than thirty years: The Odd Couple (1965), The Star-Spangled Girl (1966), Plaza Suite (1968), The Last of the Red Hot Lovers (1969), The Gingerbread Lady (1970), The Prisoner of Second Avenue (1971), The Sunshine Boys (1972), California Suite (1976), Chapter Two (1977) … on and on, up to Rose’s Dilemma in 2003, his final play (so far). Between the comedies, he maintained his winning streak with the books for the musicals Sweet Charity (1966), Promises, Promises (1968), and They’re Playing Our Song (1979) and with more than two dozen screenplays, mostly adaptations of his plays, but also original stories such as The Out-of-Towners (1969), Murder by Death (1976), and The Goodbye Girl (1977). It became a standard joke on Broadway that only Shakespeare wrote more hit plays than Neil Simon, but, actually, Simon left Shakespeare behind years ago.

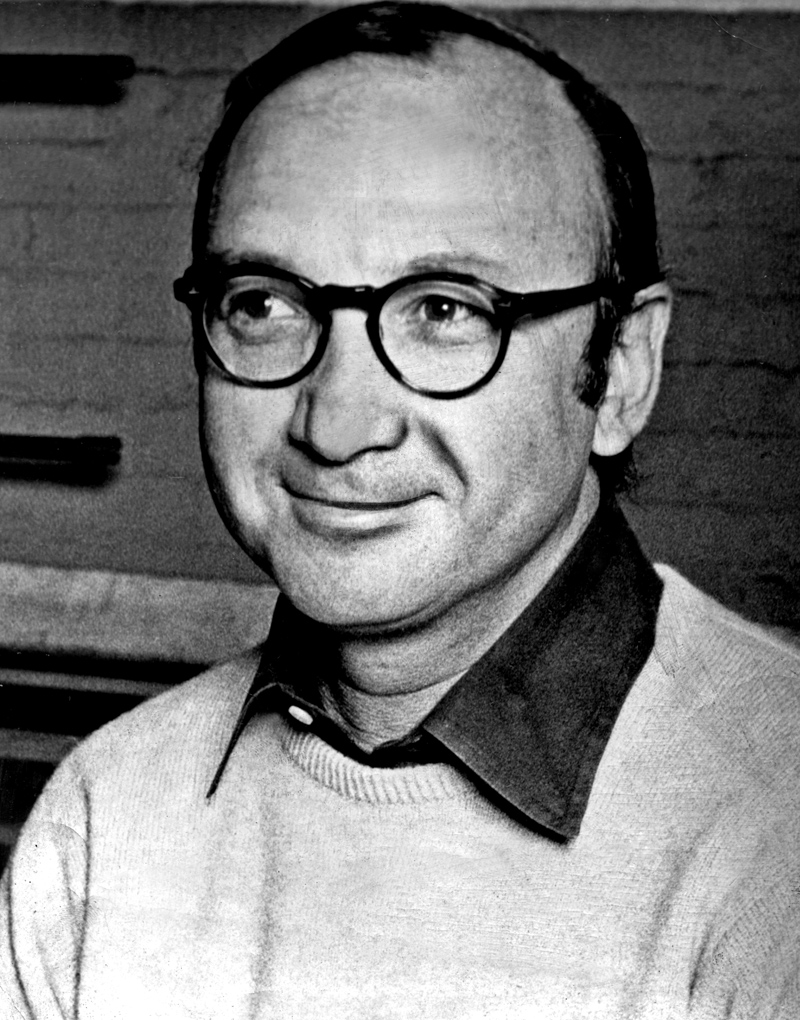

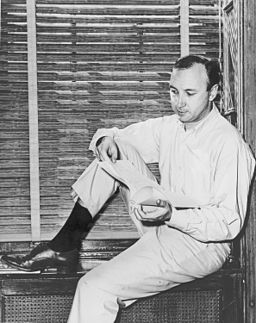

Neil Simon (1966). Photo: New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer.

The stigma of comedy writing

By general reputation, Simon was considered a lightweight; a journeyman, not a master. After all, wasn’t he just the Prince of Punchlines, the gag machine, writing frivolous entertainment for a mass Broadway audience? Surely he was too prolific, too popular and way too funny to be treated as a serious artist?

This attitude has irritated Neil Simon since the earliest years of his career. Woody Allen once said that to write comedy is to be seated at the children’s table. Simon agrees, complaining in a 1992 Paris Review interview that, except perhaps for his first play, Come Blow Your Horn, when his gag-reflex from his days in TV sketch comedy sometimes got the better of him, the laugh lines in his plays always come out of character and situation: ‘Walter Kerr [the critic] once came to my aid by saying, ‘to be or not to be’ is a one-liner. If it’s a dramatic moment, no one calls it a one-liner. If it gets a laugh, suddenly it’s a one-liner. I think one of the complaints of critics is that the people in my plays are funnier than they would be in life, but have you ever seen Medea? The characters are a lot more dramatic than they are in life.’

Jack Klugman as Oscar Madison and Tony Randall as Felix Unger from the television program The Odd Couple (1972). Photo: ABC Television.

Seeing the humour in a sad situation

If you take a good look at Simon’s sixty-odd major works, which, as well as stage plays, includes the books for musicals and more than two dozen adapted and original screenplays, there is no shortage of important and serious themes. A comedy-drama about two boys abandoned into the care of their monstrous grandmother, Lost in Yonkers was not a sudden turn towards weightier themes. He’d been handling serious issues his entire career, for the solid dramatic reason that comedy is funnier when the stakes are high. Each of the three greatest stressors in modern life – death of a loved one, divorce and unemployment – have their own hit Neil Simon play: in Chapter Two, a husband has lost his wife to cancer (as Simon had a couple of years before – there’s always been a strong streak of autobiography in Simon’s plays); The Odd Couple begins with a marriage break-up; and The Prisoner of Second Avenue is about a successful man suddenly thrown out of work. In play after play, Simon’s families are dysfunctional, his marriages are tense and unhappy, and his friendships fester with competitiveness and envy. ‘The way I see things, life is both sad and funny. I can’t imagine a comical situation that isn’t at the same time also painful. I used to ask myself: “What is a humorous situation?” Now I ask: ‘What is a sad situation and how can I tell it humorously?”’

Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple is playing from 5 November at Southbank Theatre.

Header photo: Art Carney as Felix Ungar, and Monica Evans and Carole Shelley as the Pigeon Sisters, from the original Broadway production of The Odd Couple (1965). Photo: Henry Grossman.

Published on 21 October 2016