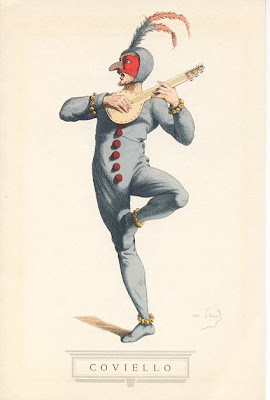

The character Coviello, illustrated by Maurice Sand.

Commedia dell’arte is shortened from ‘commedia dell’arte all’improviso’, meaning ‘comedy through the art/craft of improvisation’, but also translates as ‘comedy of the guild’; Europe’s first professional theatre. Previously, theatre had been provided by amateur academics, writing and performing their own plays (known as ‘commedia erudite’; ‘learned comedy’).

Commedia originated in Italy in the mid-16th century with companies consisting of ten or so touring players, often playing improvised outdoor venues. The more prestigious companies had patrons amongst the nobility and the rest relied on carnival organisers hiring their services, or audiences tipping them. The actors specialised in playing particular stock characters and wore masks depicting these personalities. Unlike British theatre, where Shakespeare’s heroines were being played by young male actors, commedia used actresses; attempts by the church to ban actresses for their corruptive influences never succeeded.

There were no written scripts in commedia; companies improvised their shows along predetermined plot scenarios, knowing the rough structure of the narrative. Each actor knew where their character’s story began and concluded, and therefore the various plot-points they needed to hit in order to complete their character’s journey. They memorised speeches, songs, poems and sections of dialogue so they could recall them on stage as necessary.

Commedia also had roots in the art of touring jongleurs, wandering entertainers, who performed a mix of acrobatics, songs and audience interaction (not dissimilar from the likes of contemporary street performers in London’s Covent Garden). From jongleurs, commedia inherited lazzi, comic verbal or physical set pieces, which they studied and honed, incorporating them into the action when applicable.

Goldoni’s earliest writings for the theatre consisted of sections of dialogue for the players to improvise with, but he soon recognised that in order to become a playwright like the European writers he admired such as Moliere, then he needed total control over the whole play. He began writing full scripts and banned masks which he felt were an unnecessary barrier between performer and audience, his changes met with resistance from the actors who resented handing control of their art over to a new party. Commedia as a form was 200 years old however, and becoming stale; Goldoni determined to explore real Italian life onstage, and the audiences responded. His plays often had a satirical edge, commenting on contemporary issues and relationships, and he fairly portrayed people from different classes, condemning the immoral whether they were poor or rich.

You can learn more about the key character archetypes in Commedia Dell’Arte, in the below video from National Theatre.

This article was written by Adam Penford and first appeared in National Theatre’s Education background pack for One Man, Two Guvnors.

The National Theatre’s production of One Man, Two Guvnors is playing at Arts Centre Melbourne, Playhouse from 17 May to 22 June.

Published on 6 May 2013